|

| San Francisco Vigilance Committee |

San Francisco can be seen as a lesson in what happens when people fail to perform their civic duties. Many tried “to get rich quick,” neglecting public affairs, including jury duty, so only those with an ulterior motive tended to serve on juries. For example, justice was often perverted when the only willing jurors were friends of the accused.

On the other hand, a case may be made that partisan politics was the fundamental motivating factor in San Francisco. With the Whigs defunct, Democrats divided over slavery, and Know-Nothings offensive to most voters (despite their having elected Governor J. Neely Johnson in 1855), a vacuum welcomed a new party, the Republicans. All that those with political ambitions needed was to find a cause, and the issue of law and order provided that.

Life was turbulent in San Francisco during the gold rush and early days of independence from Mexico. Without strong government, gangs roamed the streets, demanded free drinks, and abused the Latino community.

|

On 15 July 1849, when a bunch of ruffians launched a raid against the Chilean neighborhood, 230 men retaliated. They took the law into their own hands, formed a special police force, arrested the gang, elected two new judges, and appointed a new district attorney.

Two years later, after law and order was again neglected, 700 men banded together as the Vigilance Committee of 1851 to supplement local law enforcement. But, within a short time after the group disbanded, the situation returned to near anarchy. Arson, murder, and election fraud continued to go unpunished.

Two particular events sparked public concern. On 19 November 1855, a gambler, Charles Cora, shot and killed popular U.S. Marshal General William H. Richardson. Cora was apprehended but remained in jail pending trial.

Then, on 14 May 1856, San Francisco Supervisor James P. Casey, publisher of the San Francisco Sunday Times, shot and killed James King, noted banker and publisher of a rival newspaper, the Daily Evening Bulletin. Casey surrendered and sought protective custody in the county jail.

Mayor Van Ness asked a menacing crowd gathering outside the jail to disperse and ordered 300 armed volunteers, the Light Dragoons, the National Lancers, and the First California Guard to surround the area and protect Casey from the mob.

During this demonstration King’s bodyguards and some members of the 1851 committee, led by William T. Coleman, met secretly in the chambers of the Society of California Pioneers, forming the Vigilance Committee of 1856.

They required candidates to complete an application, to obtain the sponsorship of two members, to pay a fee from $1 to $20, to meet the approval of a Qualifications Committee, and to swear an oath of allegiance.

Many Catholics, who did not wish to join a secret society, swore a special oath not to take up arms against the committee, while 1,500 merchants and service providers as well as lawyers and clergymen joined. They used secret signs, grips, and passwords, responded to an alarm bell, and marched together waving banners.

For more than three months the committee enforced its brand of law and order. It set up court and maintained a jail in its downtown headquarters fortified with sandbags and two artillery pieces.

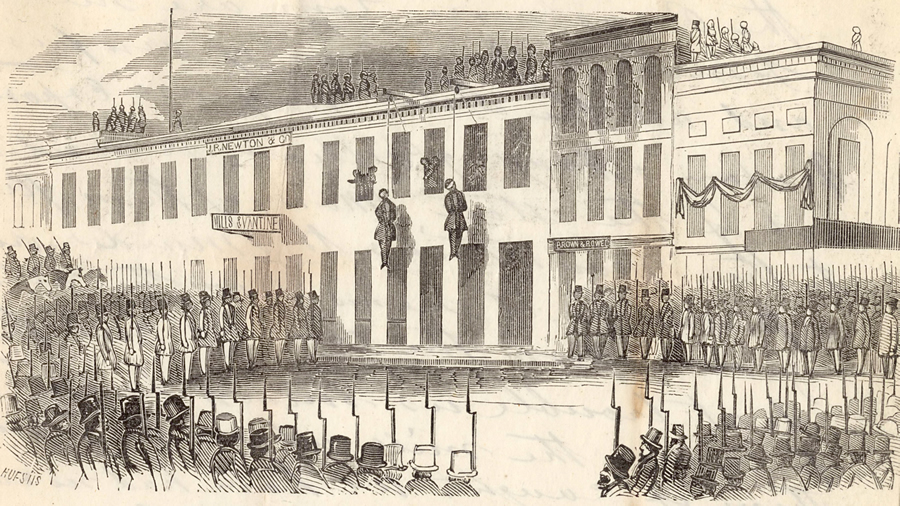

It tried and hanged four people, including Casey and Cora, contributed to the suicide of another, tried and incarcerated a state supreme court justice for stabbing one of its members, posted a $5,000 reward for the arrest of arsonists, and banished numerous rapists, thieves, abortionists, and ballot-box stuffers.

|

| Casey and Cora hanged by San Francisco Vigilance Committee |

The 5,000-man army captured four city armories and a ship loaded with weapons from a U.S. arsenal, and boarded all vessels entering San Francisco Harbor, excluding 90 percent of prospective immigrants.

On 18 August 1856, the committee disbanded, opened its tastefully decorated headquarters to visitors, and concluded with an all-day parade through the streets of San Francisco. It returned all the arms it had taken from the city, county, and state, and on 3 November, Governor J. Neely Johnson lifted his insurrection proclamation.

The committee failed in its attempt to schedule a state constitutional convention and hold special county elections, but some of its members won public office as members of the new Republican Party in November 1856, ensuring their amnesty from prosecution.