|

| Shays’ Rebellion |

The economic crisis that followed the American Revolution sparked a contraction of credit that hit poor frontier inhabitants particularly hard in the wake of shaky harvest seasons. To pay the war debt, creditors and collectors demanded specie—hard coin—instead of the inflation-prone paper money that had funded the revolution and provided debtors with reasonable means toward solvency.

Backcountry economic systems, which predominantly functioned in networks of barter rather than cash exchange, could not readily accommodate the change. As western towns exercised only the weakest influence over the Commonwealth Assembly, direct action provided their only recourse against this imposition.

Throughout the frontier, protestors shut down courts, obstructed sheriffs and tax collectors, and at rare moments took up arms to defend their understanding of economic liberty against what they understood as a Federalist plot to impose a renewed economic and political hierarchy over a newly democratic land.

|

Drawing on colonial and revolutionary methods of popular protest, resistance to the renewed surge of debt enforcement and taxation spanned the new nation from South Carolina to Maine.

While most historical accounts center on rare incidents of violence, the vast majority of this resistance proved entirely peaceable, centering on evading court appearances and obstructing sheriffs and tax men. One Pennsylvania town went so far as to erect a 4-foot-high “wall of stink” out of fifteen wagon loads of manure to defend their main road against officials.

The Regulator Movement that became known as “Shays’ Rebellion” provided a particular focal point for this struggle. Fearing a conspiracy to destabilize the new nation and the depredations of unruly “mobs,” political opponents of the resistance dubbed the western Massachusetts movement “Shays’ Rebellion” after Captain Daniel Shays, a Revolutionary War veteran who participated in the protests. Casting Shays as an insurgent leader provided the spin that the Massachusetts government needed to set off fears of despotism and rebellion against the Republic itself.

Neither led by Shays nor engaged in revolt against government, farmers organized in committees to coordinate what they termed a “Regulation” to defend the lands and liberties they claimed as a result of the Revolutionary War.

In a society where basic political rights stemmed from economic independence (primarily in the form of freehold land), foreclosures and excessive tax demands seemed to threaten the core liberties of men and women who had fought long and hard for their independence.

Regulators organized marches, harried magistrates and tax men, evaded summons, petitioned against the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, and held their own extralegal county conventions. These activities, in the making since Rev. Samuel Ely’s 1782 agitations against court and constitution, came to a head in 1786 and 1787 with a coordinated series of attacks on debtors’ courts.

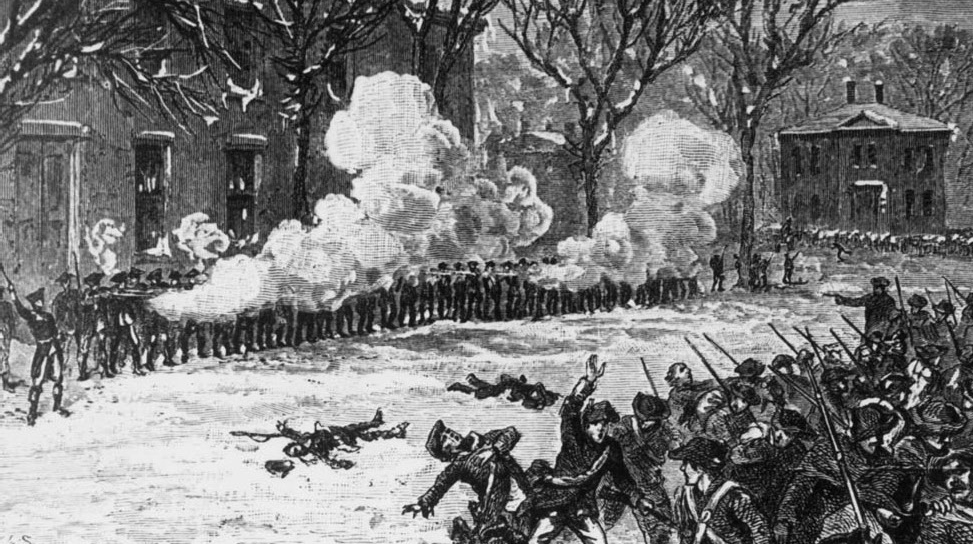

Organized in detail and conducted in large part by seasoned militia units, these aggressive protests brought national attention to the situation in western Massachusetts. Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin hired a private army to quell the disturbance, pitting poor easterners against poor westerners in an effort to restore order to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Republic at large.

After a disastrous attempt to capture the federal arsenal at Springfield, the Massachusetts Regulator Movement disbanded, torn over questions about the use of force and facing an army ready to retaliate against future action. Realizing their fears of democracy and despotism, Federalists were provided by “Shays’ Rebellion” with the catalyst they needed to advance their plan of a more powerful centralized state.

In May 1787, a collection of wealthy elites, called by private invitation, met behind closed doors and locked shutters to write a federal constitution designed, in part, to prevent such popular protest by “insur[ing] domestic tranquility.”