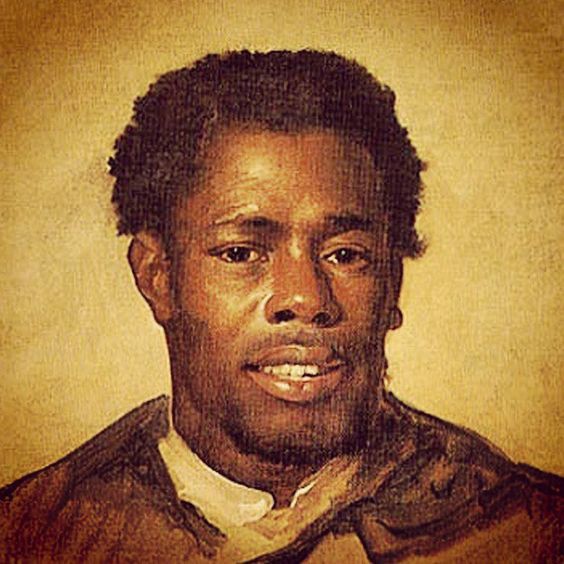

Nat Turner (1800–1831), the leader of the 1831 Southampton Conspiracy, was born in Virginia as the property of Benjamin Turner. His mother was a first-generation slave born in Africa and took care to instill a deep resentment of slavery in her son as well as to pass along traditional African customs, which included the belief in physical signs of success and greatness that she found on Nat’s face and body in the form of birthmarks.

The Turner family allowed Nat to be educated alongside their own children as a playmate and confidante, so that Nat became literate, and with great scientific curiosity conducted experiments with explosives, papermaking, and construction.

Financial failures and deaths among the Turner family, however, meant that Nat lost his favored place in the master’s family, and was inherited, sold, and traded to three different groups of relatives, each time forced to change his surname and accept the lower status of a field slave.

|

Nat’s activities soon centered around his lay preaching, based on his Methodist education but flavored with African traditions and a growing millennialism slaves found attractive, since it promised them escape from bondage.

A series of visions, beginning in 1828, led Nat to believe he was a chosen leader, meant to free the slaves in a violent war against their masters, and he cultivated the reputation of a holy man, shunning alcohol, tobacco, and rich foods.

Far from restricting his preaching and travels, the Turners encouraged Nat, since they believed Christianity helped keep the slaves subdued and obedient, and they trusted Nat to traverse the area at all hours.

During Nat Turner’s lifetime, slave revolts had been occurring with regularity, including the Andry plantation insurrection in Louisiana, the failed conspiracy of Denmark Vesey in Charleston, South Carolina, and Gabriel Prosser’s rebellion in Richmond, Virginia. Nat used his ability to read and to accumulate information in order to study these failed revolts and plan his own without their flaws.

Fearing betrayal from house servants sentimentally attached to their master’s families, Nat drew his six lieutenants from the field hands of the Turner and neighboring plantations and small farms, and organized them in independent cells, without the fatal knowledge of each other’s existence.

Plans for the coming rebellion remained in Nat’s hands, written in detail as encoded maps, lists, and prophetic statements, sometimes written on handmade paper in his own blood.

After seeing an eclipse on 13 August 1831, Nat believed he had received a sign for the rebellion to commence. His coconspirators, eager to begin, received their instructions: gather their cells of supporters and move quickly to kill all slave owners as they moved toward the county seat of Southampton, Jerusalem, leaving no one alive to warn others. En route, they would free slaves, secure supplies and arms, and eventually raise all of Virginia’s enslaved population in revolt.

The men set off in the evening of 13 August and attacked first their masters’ farms, then ranged outward, striking with great speed and discipline, killing the whites and gathering more rebellious slaves to their cause. Interestingly, the rebels spared the small farm of a poor white family without slaves, judging them to be as disadvantaged as slaves themselves.

The following morning, the bloodied bodies of the slain were discovered, triggering a panic in which whites fled their farms, often running into parties of the rebels, who slaughtered them.

The Virginia militia, hastily summoned, moved to defend the county seat and set up an outpost at Parker’s Farm, one of the last before the city of Jerusalem. The rebels scattered the first party of men they encountered, but were thrown into disarray by militia reinforcement when they attempted to pursue them.

Unable to take the arsenal at Jerusalem, the rebels attacked more outlying plantations, but had lost their advantage of surprise, and found themselves hampered by the slaves roaming the area trying to join them. The militia, meanwhile, called on federal reinforcements from Fort Monroe, and these fresh, professional soldiers skirmished successfully against the tired, hungry, and poorly supplied rebels.

|

Nat Turner, hoping to rally his forces for another assault, went into hiding at Cabin Pond, his original headquarters, but none of his lieutenants survived to join him.

Federal soldiers, joined by marines from the port of Norfolk and an enlarged Virginia militia, scoured the countryside, arresting and then executing sixteen slaves found armed and in revolt. Torture of prisoners, including Nat’s common-law wife, free blacks in Richmond, and Turner farm slaves eventually led to Nat’s surrender on 30 October after two months in hiding.

While Nat was imprisoned, his lawyer, T. R. Gray, took a careful account of his experience and the conduct of the rebellion, noting that the insurrection had not been triggered by any specific mistreatment, but was instead an outpouring of resentment and rage against the slave-holding system. Gray later published these documents as the Confessions of Nat Turner.

Nat pleaded guilty, refusing to admit any feelings of guilt for the deaths of approximately sixty slave-owning whites, and was hanged on 11 November. The state of Virginia paid his owners a compensation of $375 for the loss of their property.

The rebellion terrified slave owners and resulted in the introduction of draconian slave codes throughout the South, restricting slaves’ ability to meet in groups, punishing possession of printed materials thought to inspire rebellion, and increasing border and slave patrols.

The state of Georgia even went so far as to single out abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison as the chief instigator of the revolt and offered a reward for his death. The immediate success of Nat Turner’s rebellion was based on his ability to conceal his plans and maintain discipline among his coconspirators.

Their defeat at the hands of the militia and federal troops came only after several days, and was restricted by their inability to secure more ammunition and supplies. As a rebellion, these men compare favorably to modern guerrilla movements in their effectiveness and their ability to throw the majority population into terror and disarray.