|

| The Molly Maguires |

Twenty young Irishmen were hanged in the anthracite region of northeast Pennsylvania in the late 1870s, convicted of a series of killings stretching back to the Civil War. The convicted men were members of an alleged secret society called the “Molly Maguires,” said to have been imported from the Irish countryside, where a society of the same name was active in the 1840s.

In Pennsylvania the Molly Maguires apparently acted behind the cover of an ostensibly peaceful Irish fraternal organization called the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH)

More than fifty Molly Maguires went on trial between 1875 and 1878; twenty were executed and twenty more went to prison. The first ten Molly Maguires were hanged on a single day, 21 June 1877, known to the people of the anthracite region ever since as “Black Thursday.”

|

The Molly Maguires stood accused of killing as many as sixteen mine owners, superintendents, bosses, and workers. Their trials, conducted in the midst of enormously hostile national publicity, were a travesty of justice. The defendants were arrested by the private police force of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, whose ambitious president, Franklin B. Gowen, had financed the Pinkerton operation.

They were convicted on the evidence of an undercover detective who was accused (somewhat half-heartedly) by the defense of being an agent provocateur, supplemented by the confessions of a series of informers who had turned state’s evidence to save their necks.

Irish Catholics were excluded from the juries as a matter of course. Most of the prosecuting attorneys worked for railroads and mining companies. Remarkably, Franklin B. Gowen himself appeared as the star prosecutor at several trials, with his courtroom speeches rushed into print as popular pamphlets.

In effect, the AOH itself was put on trial: mere membership of that organization was presented as de facto membership of the Molly Maguires, and membership of either was routinely presented by the prosecution as evidence of guilt—on charges not simply of belonging to an oath-bound society but of using that society to plan and execute diabolical crimes.

Viewed in retrospect, the case of the Molly Maguires displayed many of the classic hallmarks of a U.S. conspiracy theory. Even by nineteenth-century standards the arrests, trials, and executions were flagrant in their abuse of judicial procedure and their flaunting of corporate power. Yet only a handful of dissenting voices were to be heard, chiefly those of labor radicals.

To explain why something like this could happen it is important to understand why the prosecution’s depiction of the Irish defendants seemed so convincing to contemporaries. The prosecution offered no plausible explanation of motive and nor, it seems, was one expected.

The explanation of Irish depravity was simply that the Irish were depraved by nature; they killed people because that’s the type of people they were. This argument, while perfectly circular, was a surprisingly powerful one in the United States of the mid-nineteenth century.

Irish American violence and depravity, from the labor upheavals and urban rioting of the antebellum era to the draft riots of the Civil War and the Orange and Green riots of 1870–1871, were presented as the logical transatlantic outgrowth of an alien immigrant culture.

In the United States, moreover, that culture was equipped with an international conspiratorial organization, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, whose tentacles were said to reach across both the North American continent and the Atlantic Ocean.

The inherent savagery of the Irish was the guiding premise in what passed for the first wave of interpretation of the Molly Maguires, a stream of pamphlets, newspaper reports, and histories produced by contemporaries.

Even a somewhat sympathetic observer like Dewees (The Molly Maguires: The Origins, Growth, and Character of the Organization, 1877) took the Irish propensity for violence more or less for granted, while the author of the other standard contemporary history, Allan Pinkerton—founder of the famous detective agency—took Irish depravity as his central theme (The Molly Maguires and the Detectives, 1877).

This highly pejorative and highly conspiratorial perspective, which constituted the foundational myth of the Molly Maguires, remained dominant for the next two generations, resurfacing, for example, in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Valley of Fear (1904) and providing a staple of dime novel fiction until the mid-twentieth century.

By the 1930s, however, the tide had begun to turn. Anthony Bimba, a Marxist historian, was the first to offer a major revision (The Molly Maguires, 1932), placing the Molly Maguire affair firmly in the context of labor and capital.

So concerned was Bimba to overturn the prevailing myth of the Molly Maguires, however, that he turned it on its head, retaining its elements of circularity, tautology, and conspiracy while transferring the burden of evil from Irish workers to their employers. Evil is not a very useful category of historical analysis, at least in cases like this, for it freezes time and character rather than trying to explain causation and motivation.

Why did the employers frame twenty innocent men? Because they were evil; or, put another way, because they were capitalist. At the same time, by collapsing all workers into a single category, Bimba ignored the class and ethnic diversity among them, a consideration that is now crucial to our understanding.

J. Walter Coleman, in The Molly Maguire Riots: Industrial Conflict in the Pennsylvania Coal Region (1936), was the first to open up this line of inquiry. Despite its apparently pejorative title, Coleman’s book is among the most sympathetic and convincing accounts of the subject.

The Molly Maguires, he argued, represented a specifically Irish form of labor protest, distinct from the British-inspired tradition of trade unionism in the anthracite region. If this diversity is one of the keys to understanding the Molly Maguires, another is the inherent unreliability of the evidence produced by James McParlan. He was, after all, a trained liar.

Both of these points were persuasively made by Coleman but largely ignored in Wayne G. Broehl’s The Molly Maguires (1964), which, by the standards of its time, seems curiously sympathetic to James McParlan, to his employer Allan Pinkerton, and to the employer of both, Franklin B. Gowen.

A rendition of the subject more in keeping with the radical ethic of the 1960s can be found in the film The Molly Maguires (dir. Martin Ritt 1970) starring Sean Connery as the hero (alleged Molly ringleader John Kehoe) and Richard Harris as the anti-hero (turncoat James McParlan).

It is a revealing footnote to U.S. cultural history that the director, Walter Bernstein, had been blacklisted in the McCarthy era and in part saw his film as a response to Elia Kazan, who had notoriously “named names” in the 1950s, and whose hero in On the Waterfront informs against his corrupt union bosses.

How, then, is one to make sense of the Molly Maguires? Clearly, what is needed is an explanation that can break free of the two existing poles of interpretation: the Molly Maguires as depraved killers and the Molly Maguires as innocent victims of oppression, whether economic, religious, or ethnic.

The Mollys themselves, being socially marginalized and largely illiterate, left us virtually no evidence, which exposes the subject to all manner of conspiracy theories, from both the Right and the Left. We do, however, have plenty of evidence about them left by other people: employers, Catholic clergymen, politicians, newspapermen, pamphleteers, census takers, government officials, and contemporary historians.

Read carefully, these forms of evidence can yield at least some reliable information about who the Mollys were. Equally important, they can tell us a great deal about the aims and motivations of those who set out to destroy them. In the end, though, some fundamental historical questions demand at least a tentative answer: Who were the Molly Maguires, what did they do, and why?

The starting place in seeking an answer to these questions is the country where the Molly Maguires originated. To the historian familiar with Ireland as well as the United States, the most striking aspect of the activities in Pennsylvania is how clearly they conformed to a pattern of violent protest evident in the Irish countryside from the mid-eighteenth century onward.

The Molly Maguires, who emerged toward the end of the Great Famine (1845–1851), were so named because their members (invariably young men) disguised themselves in women’s clothing, used powder or burnt cork on their faces, and pledged their allegiance to a mythical woman who symbolized their struggle against injustice.

The American Mollys were evidently a rare transatlantic outgrowth of this pattern of Irish rural protest. Contrary to contemporary conspiracy theories, however, it is highly unlikely that there was any direct continuity of organization or personnel between Ireland and Pennsylvania.

There is no evidence at all that a conspiratorial organization was somehow imported into the United States by Irish immigrants, nor is there any evidence that individuals convicted in Pennsylvania had been involved in violent activities in Ireland.

The immigrants did arrive, however, with a cultural memory and established social traditions. Faced with appalling conditions in the mines of Pennsylvania, they responded by deploying a specifically Irish form of collective violence against their enemies, up to and including assassination.

To that extent, the American Molly Maguires clearly did exist, even if they never existed as the full-fledged diabolical organization depicted by contemporaries. They were not purely a figment of the conspiratorial imagination; indeed the conspiracy theories about them could have achieved little credibility if Irish workers had not been engaged in collective violence of some sort.

There were two distinct waves of Molly Maguire activity in Pennsylvania, one in the 1860s and the other in the 1870s. The first wave, which included six assassinations, occurred during and directly after the Civil War.

Nobody was convicted of these crimes at the time, although a mysterious group called the Molly Maguires was widely believed to be responsible. Only during the trials of the 1870s were the killings of the previous decade retrospectively traced to individual members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians.

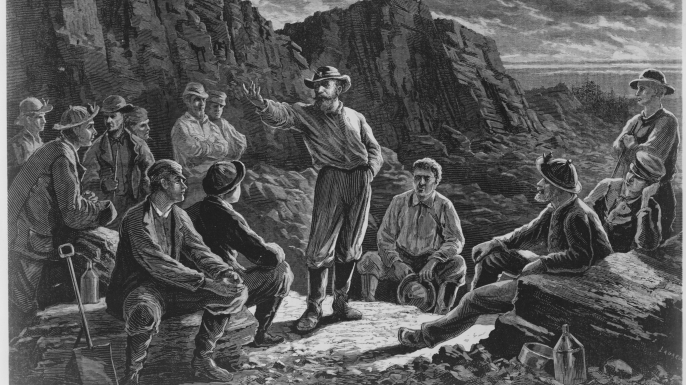

At the heart of the violence in the 1860s was a combination of resistance to the military draft with some form of rudimentary labor organizing by a shadowy group known variously as the “Committee,” the “Buckshots,” and the “Molly Maguires.” During the crisis of the Civil War, all forms of labor organizing were seen as potentially seditious.

The second wave of violence did not occur until 1875, in part because of the introduction of a more efficient policing and judicial system, but mainly because of the emergence of a powerful new trade union, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA), which united Irish, British, and U.S. workers across the lines of ethnicity and skill.

The labor movement of the anthracite region now took two distinct but overlapping forms: a powerful and inclusive trade union movement, half of whose leaders were Irishborn; and an exclusively Irish and largely unskilled group of workers called the Molly Maguires.

Favoring collective bargaining, strikes, and peaceful reform, the leaders of the WBA publicly condemned violence, singling out the Molly Maguires specifically. Yet Franklin B. Gowen repeatedly insisted that the WBA was simply a cover for the Molly Maguires, who constituted the union’s terrorist arm.

Although this claim was manifestly false, it was highly effective; by collapsing the distinction between the two organizations Gowen succeeded in destroying the power of both. Not only was the union discredited by this strategy, the Molly Maguires were equipped with an institutional structure they never had. The defeat of one would now entail the defeat of the other.

To gather information against both arms of the labor movement, Gowen hired Allan Pinkerton in October 1873. Pinkerton dispatched James McParlan to the anthracite region. Several other agents would follow later. Shortly after McParlan fled the anthracite region, in spring 1875, matters reached a climax. After a heroic six-month strike against Gowen and his railroad, the WBA went down to final defeat.

In the disarray that followed, the Molly Maguires stepped up their activities to a new level: six of the sixteen assassinations attributed to them took place in the summer of 1875, even as the leaders of the now-defunct trade union continued to voice their condemnation. In January 1876 the arrests began, and that summer the famous trials commenced.

With labor utterly defeated, Franklin B. Gowen completed his conquest of the local economy, securing full control over production and distribution in the lower anthracite region. This was the goal the trade union and the Molly Maguires had long threatened, and it is quite clear that Gowen had been prepared to take all necessary means to eliminate that threat.

For almost a century nobody in the Pennsylvania anthracite region was willing to say much about the Molly Maguires. The story was too painful, too divisive. Not the least remarkable aspect of this ongoing story, however, has been a dramatic renewal of interest in the anthracite region itself.

Every June 21 for the last six years several hundred people have arrived in the mining region to commemorate the Molly Maguires. Descendants of the convicted men and their alleged victims have sat down together to eat, drink, and talk.

The dominant note of each year’s gathering has been how to include all sides and perspectives. This ecumenical spirit, so clearly lacking in the 1870s, provides the best chance today of understanding one of the more tragic tales in the history of U.S. labor.