|

| Whiskey Rebellion |

In October 1794, President George Washington called out roughly 13,000 militia men from Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania to march to Pittsburgh and crush an armed rebellion against federal tax collectors in western Pennsylvania.

Washington, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, and fellow members of the governing Federalist Party were convinced that certain popular “republican” societies were conspiring against the administration.

The Federalists feared that local organizations, hostile to federal policies, were secretly fomenting open rebellion among disgruntled farmers and distillers in the rural counties west of the Allegheny Mountains.

|

The events leading up to muster of troops resulted from a series of clashes between farmers and tax collectors over an excise tax on whiskey. Hamilton ostensibly launched the tax in 1791 to pay for debts incurred during the American Revolution and for the protection of settlers on the western frontier.

For the backwoods farmers of western Pennsylvania, Hamilton’s tax seemed overly burdensome and evidence of an eastern conspiracy among wealthy elites and the government. The farmers needed to distill their grain into whiskey, or “Monongahela Rye,” as an economical way to transport their produce across the Allegheny Mountains to profitable markets in the east.

Due to a shortage of money in the west, whiskey also served as a form of currency in the rapidly expanding frontier. This taxation brought to the forefront western resentment of the economic power maintained by the government and the wealthy east of the Alleghenies. The tax seemed to be a direct assault on the economic lifeblood of the area.

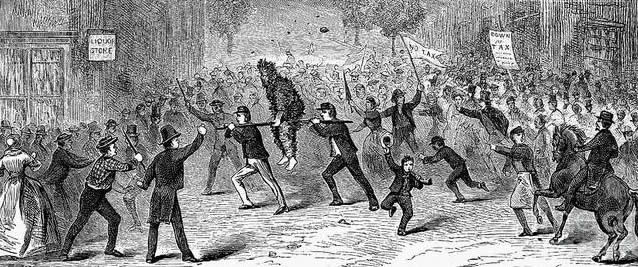

Not to be intimidated, farmers often responded by tarring and feathering local collectors, destroying compliant stills, and routinely blocking roads to the east with piles of manure, ditches, and fallen trees (Bouton). Over the next three years, tensions increased as those who did not comply were threatened with fines and imprisonment.

The “Rebellion”

By the summer of 1794, opposition to the tax had become increasingly violent and solidified against federal authority. On 16 July in Washington County, a mob of angry farmers attempted to destroy records of the fines and taxes they owed by laying siege to and eventually burning the house of federal collector General John Neville.

In an ensuing gunfight, two of the insurgents were killed. On 23 July, these farmers met with the “Mingo Creek Society” and other residents of the area to solidify their position against the federal government.

It was decided, largely at the request of lawyer and author Hugh Henry Brackenridge, to wait until August when a more formal meeting could be called to assess the collective will of western Pennsylvania. However, ten days later, some of the insurgents intercepted and read U.S. mail from citizens in nearby Pittsburgh to determine the town’s attitudes toward the rebellion.

Some of the letters were written to prominent Federalists and contained threats against the insurgents and denunciations of their cause. The insurgents were outraged. Under the leadership of self-appointed general David Bradford, a prominent but eccentric lawyer, they proposed a march on Pittsburgh to capture and imprison those who had written the letters.

By this time, the whole of western Pennsylvania had heard about the killings at Neville’s house and, in response to a general muster called by Bradford, approximately 7,000 men turned up on 1 August at Braddock’s Field outside Pittsburgh, ready to march on the town.

Largely through the negotiations and delay tactics of moderates like Brackenridge and the quick-thinking Pittsburghers (they fed and welcomed the insurgents as they paraded through the streets), the rebels had little energy for destroying the town by the time they marched. Only a few houses were looted, and the barn of General Neville’s son was burned. By the end of the day, less than 100 of the “whiskey rebels” remained in Pittsburgh.

Federal Reaction

On 7 August Washington issued a proclamation that detailed his interpretation of the events leading up to the rebellion, blaming “certain irregular meetings” and “combinations” in Pennsylvania’s western counties for creating unrest among the farmers. The Federalists publicly sought a peaceful solution by dispatching a commission to negotiate an end to the rebellion.

Tensions lessened, and the majority of westerners favored reconciliation. However, there were still sizable numbers of radicals advocating rebellion, and while negotiations continued through August, Hamilton and Washington secretly prepared for war.

Seeking a show of federal strength and worried that “committees of correspondence” were trying to unite conspirators against the union in other western states, Hamilton asked Governor Henry Lee of Virginia to secretly draft a 12,950-man army and postdate his orders to 1 September so that it would appear the government had sought a peaceful solution in good faith.

By the end of September, the commission, unable to reach complete reconciliation with the farmers, asked Washington to send troops to western Pennsylvania. But when the troops eventually reached Pittsburgh at the end of October, the rebellion had subsided through the efforts and negotiations of moderates (Brackenridge).

Hoping to maintain peace and support for the federal government, Washington magnanimously pardoned the known insurrectionists, with the exception of David Bradford, who escaped down the Ohio River in a canoe to Spanish territory.

Analysis

While historians recognize the Whiskey Rebellion as the first great test of America’s federal government against subversion, they also suggest that the “conspiracy” accusations launched by Federalists and rebels alike were really passionate reactions to a number of social, political, and economic factors central to the new Republic.

To the whiskey rebels, the government was unfairly generating revenue from produce grown in the west instead of taxing the eastern land speculators who actually owned much of the western Pennsylvania farmland the grain was grown on. The tax, in their estimation, was proof that the government was conspiring with economic and political elites in Philadelphia and the east to oppress the western country.

Scholarship does suggest that Hamilton initially launched the whiskey tax as an ideological power play, designed to prove the federal government could tax anywhere within its boundaries. He welcomed the rebellion as a way to display the integrity of the newly formed federal system and show its ability to enforce domestic policies (Slaughter).

From the federal side, Washington’s accusations that the Whiskey Rebellion was part of a larger western conspiracy against the government indicate a fear early Anglophile Federalists entertained that the liberalism and violence of the French Revolution would spill over into the less “civilized” populace of America.

The existence of several Francophile political societies (some established by French foreign minister Edmond Genet) in Philadelphia and the western states (Koschnik) was evidence enough to convince Washington that a network of subversives was at work to undermine the Federalists’ power.

While much of the resistance to the tax was random and loosely organized, some western Pennsylvanians, following the lead of Philadelphia, did create Jacobin-like “Republican societies” for the purpose of reducing federal power, and the whiskey tax was a perfect rallying point for them.