|

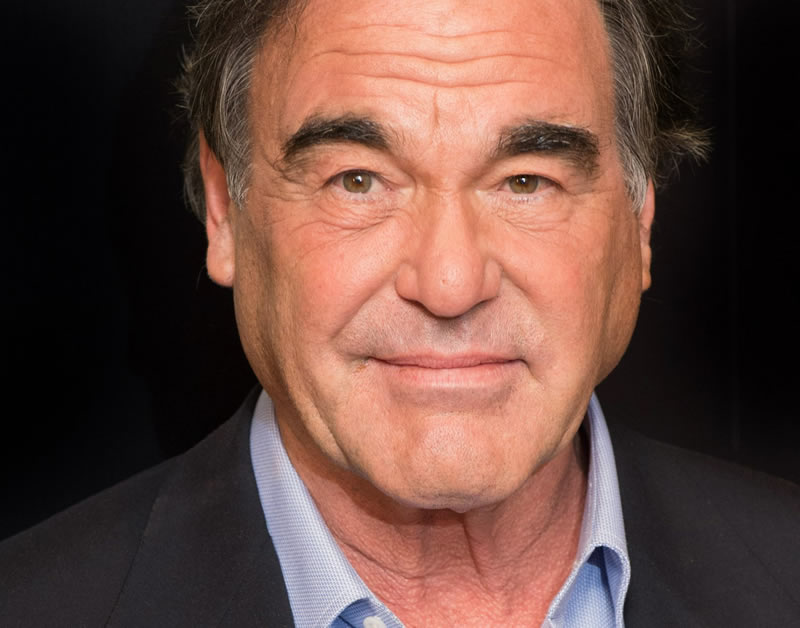

| Oliver Stone |

Oliver Stone is a filmmaker whose politically charged films have often provoked controversy. However, Stone’s 1991 film JFK, a docudrama centered upon New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s investigation during 1967–1969 into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, is undoubtedly the most controversial of Stone’s works. In fact, no other film in U.S. cinema history has attracted quite the same level of critical outrage and scrutiny as JFK did before, during, and after its theatrical run.

Given the negative media coverage of Garrison’s failed attempt during the late 1960s to convict New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw of conspiracy in the murder of President Kennedy, it is not surprising that a film that recasts that same event in a manner much more favorable to Garrison, and further accuses most of the governmental apparatus of the United States of murdering its own president, would create yet another media tumult.

Stone’s early life in many ways had prepared him for such public combat. He was born on 15 September 1946 in New York City to a Jewish stockbroker father and a French Catholic mother whose marriage ended in divorce.

|

Stone entered Yale in 1965 but dropped out after one year and moved to Vietnam and then Mexico. In 1967, Stone joined the army and returned to Vietnam as a solider. He served fifteen months in the 25th Infantry Division, where he was wounded twice. Upon his return to the United States in 1968, he entered New York University Film School.

His subsequent film career included screen-writing credit for Midnight Express (1978) and Scarface (1983) and directorial credit for The Hand (1981), Salvador (1985), Platoon (1986), Wall Street (1987), Talk Radio (1988), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), and The Doors (1991).

During this productive period, Stone read Jim Garrison’s 1988 book, entitled On the Trail of the Assassins, about the investigation and trial of Clay Shaw. Stone believed that Garrison’s narrative could form the basis of a powerful film.

Inspired by the book, Stone began his own investigation into the intellectual netherworld of JFK conspiracy theories to augment Garrison’s story. Stone purchased the rights to Jim Marr’s book Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy (1991) and hired a Yale graduate named Jane Rusconi to assemble a team of researchers and interviewers. Stone and his team thus joined the ranks of those who had long sought to establish the existence of a conspiracy to murder the thirty-fifth president.

Almost since the moment the president was killed in Dallas, conflicting eyewitness accounts suggested that shots were directed at the presidential motorcade from more than one direction (most infamously, from the grassy knoll in front of the president’s limousine).

The 1964 Warren Commission, formed to investigate the truth behind the shooting, produced a twenty-six-volume report that named Lee Harvey Oswald as the sole assassin of the president but instantly generated intense criticism of its conclusions from early assassination researchers such as Mark Lane, Josiah Thompson, Sylvia Meager, and Harold Weisberg.

The untimely deaths of many participants or witnesses to the events fostered a climate of mystery and paranoia that only aggravated researchers’ feeling that something sinister was afoot.

In the years following the assassination, the public followed the early skeptics’ lead and a majority increasingly came to believe that a conspiracy, not just a lone gunman, had killed President Kennedy. Even the United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations in 1979 concluded that Kennedy “was probably assassinated as the result of a conspiracy.”

Stone and co-writer Zachary Sklar then began incorporating all of these disparate elements into a lengthy screenplay (first draft of 190 pages), which in its final form is a distillation of most of the varied conspiracy theories advocated by assassination researchers over the years.

Beginning in 1990, Stone also met with a former colonel and Pentagon chief of special operations named Fletcher Prouty, whose career and theories about the motives behind the assassination provided the inspiration for one of the film’s most important informants. Securing studio backing from Warner Brothers in 1989, Stone proceeded to active production, filming, and post-production during 1990 and 1991.

JFK in its final form is primarily a murder mystery based in part on Garrison’s memoirs of the investigation and trial of Clay Shaw and further incorporating various aspects of Stone’s own research into the presidential assassination. As the cinematic narrative unfolds, authentic footage is frequently and rapidly intercut into the film’s re-creation of historical events to give the movie its startling verisimilitude.

As Chris Salewicz observes, the film also interweaves at least four separate storylines in an impressionistic, almost stream-of-consciousness manner, influenced heavily by the multiple perspectives in Akira Kurosawa’s famous 1950 film Rashomon and the 1969 Constantin Costa-Gavras political film Z (Salewicz, 81). JFK begins with a prologue depicting the election, presi- dency, and assassination of President Kennedy.

Then the film shifts to Garrison’s investigation of a New Orleans connection to supposed assassin Lee Harvey Oswald—a connection that ultimately implicates private detective and ex-FBI agent Guy Banister, homosexual former Eastern Airlines pilot David Ferrie, and Clay Shaw.

Garrison gradually becomes convinced that these men are part of a larger, rightwing conspiracy directed against President Kennedy and comprising a devil’s brew of anti-Castro exiles, Mafia gangsters, the CIA, military intelligence, and even the Lyndon B. Johnson White House. Garrison concludes that Oswald, slain in Dallas in 1963 by gangster Jack Ruby, was a patsy, set up to look guilty by the larger forces behind the president’s shooting.

As Garrison retraces the Warren Commission investigation and tries to build a case against David Ferrie and Clay Shaw, Garrison is continually stymied by staff defections, governmental interference, media scorn, and even the mysterious deaths of key figures such as David Ferrie.

Only Clay Shaw survives to be arrested and tried for the murder of the president. However, given the insurmountable obstacles arrayed against Garrison, the trial’s outcome is a foregone conclusion. Shaw is acquitted, but Garrison vows to continue the crusade to bring Kennedy’s killers to justice.

Garrison, portrayed by Kevin Costner as a relatively uncomplicated seeker after the truth, obviously believes in the merits of his case, even if few others do. Since the film is portrayed from Garrison’s point of view and those of the people he interviews, his conclusions may appear to be presented as absolute fact to the undiscriminating viewer.

But the film is ultimately more complex than it seems, as Susan Mackey-Kallis observes, because it searches “for the ‘truth’ with the realization that there is no single, ultimately knowable truth about the Kennedy assassination” (Mackey-Kallis, 38).

Indeed, JFK raises more questions than it solves. The film considers several possible conspiracies in the assassination but finally suggests that President Kennedy was killed in a coup d’état organized by a shadowy U.S. cabal of governmental and industrial concerns.

In a covert meeting in Washington, D.C., a government informant based on Fletcher Prouty (“Colonel X”) tells Garrison that this cabal’s primary agenda was to profit from an escalation of war in Vietnam.

Through X, the film postulates that Kennedy’s refusal to support the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1963, and his intention to abolish the Central Intelligence Agency and diminish the power of the military-industrial complex by withdrawing advisors and troops from Vietnam during a second term of office, resulted in his murder by those committed to wartime militarism. Yet careful attention to the film reveals that no matter how persuasively argued or visualized, the theories proposed by X or even Garrison remain conjecture, not absolute fact.

Stone himself claims that JFK is deliberately designed as a “counter-myth” to provoke scrutiny of the official “myth” of the Warren Commission’s conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in shooting President Kennedy from the sixth floor of the Texas Schoolbook Depository.

In this goal of reopening a national dialogue about a possible conspiracy behind the Kennedy assassination, Stone succeeded beyond all expectations. His success also placed him at the center of a media and political firestorm.

Stone was denounced and vilified by numerous high-profile media and governmental critics even before JFK’s public premiere. After an early draft of the screenplay was leaked, Washington Post writer George Lardner, Jr., and Chicago Tribune writer Jon Margolis began attacking JFK in May 1991, before the film’s winter release. Other negative articles appeared during the film’s post-production phase.

As the film opened, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the San Francisco Weekly, the Chicago Sun Times, the Dallas Morning News, the Wall Street Journal, the L.A. Times, and Time and Newsweek magazines all weighed in repeatedly with decidedly negative appraisals of Stone’s film, in essence labeling it demagoguery. For example, Newsweek ran a cover story headlined, “Why Oliver Stone’s New Movie Can’t Be Trusted.”

The New York Times in particular devoted much column and editorial space to the assault on the movie. Noted journalists, commentators, media figures, and politicians joined forces to savage not only the film’s conspiracy theories but seemingly the director himself.

Writers Alexander Cockburn, Tom Wicker, and George Will; film critic Leonard Maltin; director Nora Ephron; president of the Motion Picture Association of America Jack Valenti; former U.S. President and Warren Commission member Gerald Ford—all went on the record as strongly, almost viscerally, opposed to Stone and his project.

These and other critics insisted that Stone heavyhandedly distorted history, invented characters that never existed and slandered others that did, mixed speculation and fact to an irresponsible degree, and unfairly influenced younger audience members whose exposure to history presumably came only from the simplistic exaggerations of television and film.

Some critics insisted that the film was homophobic in its depiction of David Ferrie and Clay Shaw as homosexual. Also troubling to many critics was the film’s flattening of the complex, tarnished character of the real-life Jim Garrison.

Frank Beaver calls the cinematic Garrison a “representational icon rather than a human being—in the end, a symbolic teacher lecturing a class” (Beaver, 172). Most journalists reporting on the real trial of Clay Shaw regarded the prosecution as a ludicrous farce perpetrated by a grandstanding, publicity-seeking, and quite possibly corrupt district attorney.

Allegations of underworld connections, illegal gambling, and witness tampering and bribery persistently dogged Garrison’s career as district attorney and, later, elected judge. Even many conspiracy theorists believed that Garrison’s true agenda in the trial of Clay Shaw had been to divert attention away from a Mafia connection to the assassination.

Stone was not unaware of the negative sentiment about Garrison (in fact had even confronted Garrison about these charges early in the process of researching JFK) but chose to disregard them, as he was making a film about the conspiracy to kill Kennedy, not a biography of Jim Garrison.

But to see Garrison practically sainted by Stone’s version of events and played as a straight arrow by Kevin Costner in the best Jimmy Stewart/Frank Capra tradition was likely more than some critics could bear.

Stone did have his share of media supporters, such as Garry Trudeau, Garry Wills, Norman Mailer, David Denby, and David Ansen, but at first the negative press far outweighed the positive.

Stone defended himself in various public and media forums, and eventually his lonely campaign began to pay off. Even as the editorial elite pounded him, public sentiment shifted toward Stone. He began meeting with congressmen to advocate the release of sealed assassination files.

Also, in response to the widespread charge that Stone had distorted or fabricated fact for the movie, Stone and Zachary Sklar published JFK—The Book of the Film, in 1992. The book contained the annotated screenplay, extensive sources and references, and pro and con commentaries by the film’s supporters and critics.

The film itself, after an initially slow box-office start, became a commercial success. It was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including best picture and best adapted screenplay, and won two in the categories of film editing and cinematography.

JFK personally garnered Stone a Golden Globe Award for best director, and Director’s Guild of America and Academy Award nominations for best director, as well as political and civic recognition such as the Torch of Liberty Award from the Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

Eventually, the film’s publicity resulted in the token release of a few formerly secret files and culminated in the congressional Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, which released many of the previously classified government documents related to the assassination.

Although the released records provided no conclusive evidence of an assassination conspiracy, enough tantalizing clues emerged to provide conspiracy researchers with more fodder for their particular theories. JFK thus joins the relatively rare ranks of films that have inspired direct political action.

The film’s notoriety also revitalized the political conspiracy thriller genre. Throughout its history, U.S. cinema had often trafficked in conspiratorial or even paranoid topics, often by depicting dastardly external enemies such as Communists or even inhuman ones such as body-snatching space aliens.

However, in the political conspiracy genre entries of which JFK is the apotheosis, the fascistic threat is even more insidious, as it originates from within the very social institutions charged with protecting democracy and the American people.

Even the president of the United States, JFK tells the audience, is a helpless (and disposable) pawn of such forces. This view displaces the individual and assigns power to a decentralized, self-contained system lethal to the kind of humanistic values touted by Kennedy in his university address during the film’s prologue.

Stone’s sweeping indictment of what his cinematic alter ego Garrison calls “the ascendancy of invisible government” went much further than any previous film had done. The public acceptance of JFK’s grim message illustrates dramatically just how entrenched the mistrust of governmental institutions had become since the great disillusionments of the 1960s and 1970s.

Nevertheless, in the decade since JFK’s release, much of the assassination controversy has subsided. (In the wake of the September 11 terrorist attack upon the United States, the film’s antimilitarism message may even seem momentarily out of favor.)

Norman Mailer’s fictional biography, Oswald (1995), faded quickly from sight, and Gerald Posner’s book Case Closed (1993) seemed to satisfy most media observers, if not the public, that Oswald was indeed the lone assassin.

Meanwhile, Stone has weathered other controversies over his films Natural Born Killers (1994) and Nixon (1995). Both films ventured into some of the same thematic and stylistic territory as JFK. Nixon created a minor flare-up among many of the same political and editorial elite who had been outraged by JFK.

Stone’s second presidential film portrays Richard M. Nixon as a hapless figure caught up in tangential involvement with the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, assassination attempts against Castro, and escalation of the Vietnam War, all of which are central to JFK and ultimately conspire, in Stone’s rendition of history, to topple the Nixon regime in the Watergate scandal. But mostly because of JFK, Oliver Stone’s name has become synonymous with “conspiracy theory.”