|

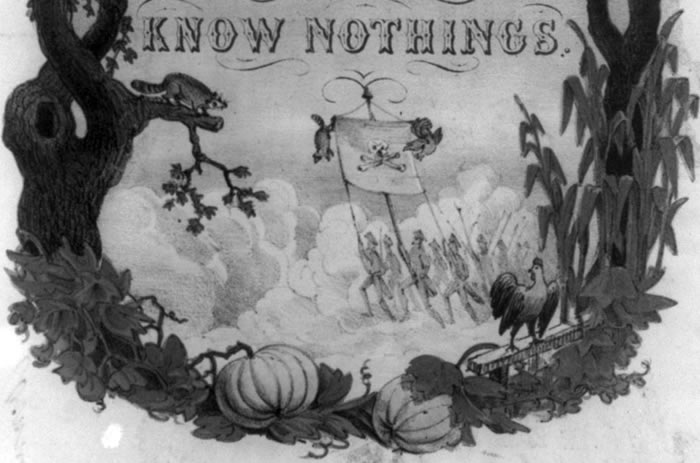

| Know-Nothings |

The American Party, or Know-Nothing Party, developed in the context of the increasing sectional tensions that led to the Civil War. An exclusive, native Protestant, anti-immigrant, and anti-Catholic organization, it stemmed from the nativist movement and from the anxiety caused by the massive influx of immigrants, reaching its peak in the 1850s.

The Papal Plot

Foreign immigration led many conservatives to believe that the nation’s social and even political ills could be solved by the elimination of foreign influence. The country had experienced an unprecedented flow of immigrants in the mid-nineteenth century, reaching dazzling numbers.

From 1841 to 1860, more than 4 million immigrants arrived, with two notable peaks: 369,980 in 1850 and 379,000 in 1851, the majority of whom were Irish (1.2 million) and German (more than a million). In cities such as Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and St. Louis, immigrants outnumbered native-born citizens.

|

Many feared the impact on the very fabric of the United States of such large groups, impoverished, ignorant, disease ridden, and alien in their religion and languages. From a political point of view, many traditional parties were distressed by the growing political influence of those groups in big cities, especially Catholics, since many of these immigrants tended to be manipulated by urban democratic political machines.

Consequently, there developed a strong belief in a papal plot to subvert U.S. values and even destroy U.S. institutions and cultural homogeneity. In addition, Catholics were deemed unfit to live in a republic and unpatriotic because they owed allegiance to the pope.

The Irish were especially blamed as tools used by the pope to control U.S. religious and political life. Moreover, the great number of Catholics moving to the Midwest caused the Know-Nothings and other nativists to think that the power of the pope might be transferred there.

By the end of the 1840s, several nativist secret societies were formed to protect and save the country, supposedly threatened by an alien menace. In 1849, Charles Allen, a New Yorker, formed a secret fraternal society made up of native-born Protestant working men, artisans, and small businessmen, who feared economic competition from cheaper immigrant labor.

It was called the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, and evolved into a secret political movement (with a formal pledge of secrecy) known as the American Party, formed in 1854 by delegates from thirteen states. If questioned, members were required to say, “I know nothing,” hence the popular appellation. They pledged never to vote for any foreign-born or Catholic candidate.

Know-Nothings made wide use of newspapers and periodicals for their propaganda, together with a network of activists from Boston to the Mississippi Valley. Some predicted that the pope and his army would land on U.S. shores to set up a new Vatican in Cincinnati, Ohio.

One famous Know-Nothing was Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, who wrote a series of articles denouncing a “foreign conspiracy.” Another was Lyman Beecher, a seventh-generation Puritan preacher. Intent on stopping the West from becoming Catholic country, he wrote that he came to Cincinnati “to battle the Pope for the garden spot of the world.” Mob attacks on Catholic churches in New England soon became frequent.

Popularity without Long-lasting Results

In practice, the Know-Nothings’ political aims were not so much to suppress immigration, nor even restrict it—although some sponsored resolutions to bar paupers and criminals—but to control the influence of foreigners and “purify” U.S. politics.

Their legislative program called for the exclusion of foreigners and Catholics from public office, for more stringent naturalization laws (extension of the residency period before naturalization from five to twenty-one years), for literacy tests as a prerequisite for voting, and for restrictions on liquor sales.

The Know-Nothings capitalized on the Compromise of 1850 and the furor over “Bleeding Kansas,” which led to a fundamental political realignment in the mid-1850s, winning national prominence chiefly because the two major parties—Whigs and Democrats—were at that time breaking apart over the slavery issue.

By 1855 they had captured control of the legislatures in parts of New England and were the dominant opposition party to the Democrats in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

In the presidential election of 1856, the party, by then mainly composed of southerners as a result of the internal debates over slavery, supported former Whig president Millard Fillmore with a simplistic platform—reputedly the shortest in U.S. history: “America must rule America.”

When the vote was counted, Fillmore gathered nearly one million popular votes (21 percent of the popular vote) and eight electoral votes. In Congress, the party had five senators and forty-three representatives.

Afterwards, Know-Nothingism declined for internal reasons: lack of efficient organization, the sudden decline in immigration, the failure to push any legislation against immigration and Catholics, disagreement over secrecy, and the mounting violence of its supporters (rioting and bloodshed took place during the elections).

The slavery issue broke down the party, as was the case for the Whigs and the Democrats. In 1855, at the party’s first convention in Philadelphia, when southern delegates pushed a resolution to support the Kansas-Nebraska Act, northern delegates left the room.

While northern workers felt more threatened by the southern Slave Power than by the pope and Catholic immigrants, at the same time, fewer southerners were willing to support a party that ignored the question of the expansion of slavery. By 1860, many members and sympathizers joined the ranks of the growing Republican Party with a political platform based on free soil.

In fact, both parties overlapped ideologically; their supporters both believed in conspiracy, one being the pope’s, the other the slaveholders’. However, historians have debated whether the inevitability of the Know-Nothings’ decline in favor of Republicanism was because the papal plot was less plausible than the slaveholders’ conspiracy.

The anti-immigration stance of the party was condemned by many Americans, like Abraham Lincoln, who frowned on their discriminatory and exclusionist philosophy as betraying such sacred U.S. values as equality and hospitality to immigrants; or William H. Seward, who attacked their failure to see that U.S. economic development required immigrants.

In 1855, Abraham Lincoln wrote in a private letter: “I am not a KnowNothing.... As a nation we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.’”

The Know-Nothings left an indelible mark on U.S. politics. The movement eroded loyalty to the national political parties, was instrumental in the breakdown of the Whig Party, and made the political system more fragile before the divisive issue of slavery.