|

| Red Summer of 1919 |

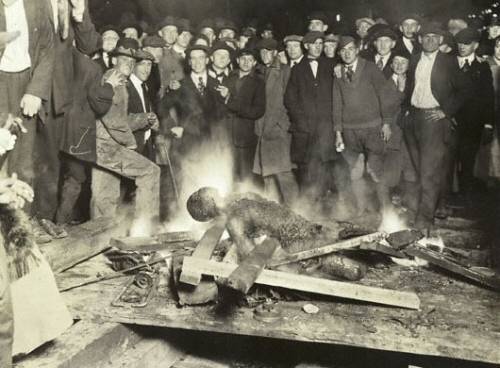

In the long summer of 1919, from May to October, an unusual pattern of white mob violence swept across the United States. As the world had begun to recover from the years of World War I, there was a great deal of social unrest in the United States. Among the general population there were class and race tensions.

Among governmental officials there were political tensions and turf wars as departments tried to justify their existence in the postwar economy. The first “red scare” was inflamed by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, while labor unions went on strike, and a series of letter bombs were mailed to prominent government figures.

It was in this climate that at least twenty-seven incidents of white mob violence erupted. Often referred to as “race riots,” these incidents were scattered throughout the continental United States, in locations that varied from major cities like Chicago, Illinois, and Washington, D.C., to smaller cities such as Omaha, Nebraska, and Knoxville, Tennessee, to rural areas like Longview, Texas, and Elaine, Arkansas.

|

Representative Leonidas C. Dyer’s Anti-Lynching Bill, introduced in the House in May of 1920, lists the riots as Bisbee, Arizona; Elaine, Arkansas; New London, Connecticut; Wilmington, Delaware; Washington, D.C.; Blakely, Georgia; Dublin, Georgia; Millen, Georgia; Putnam County, Georgia; Bloomington, Illinois; Chicago, Illinois (2); Corbin, Kentucky; Homer, Louisiana; New Orleans, Louisiana; Annapolis, Maryland; Baltimore, Maryland (2); Omaha, Nebraska; New York City; Syracuse, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Charleston, South Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee; Memphis, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; Port Arthur, Texas; and Norfolk, Virginia. More than 100 people were reported killed, and more than 1,500 people injured.

These incidents differed in several ways from the long-standing traditional practice of lynching: the perpetrators of the action were not just a small group of adult male vigilantes, but included a wide range of townspeople, male and female, adults and youths; their target was not a specific person, but rather the local black community in general; and the black community in many cases fought back, to a level unprecedented at that time.

James Weldon Johnson called it the “red summer.” And while many people suspected a conspiracy at work, there was as much disagreement about the nature of the conspiracy as there has been disagreement about whether Johnson meant “red” as in blood or “red” as in Bolshevik.

|

| Red summer map |

One of the most popular theories favored by government officials to explain the violence was that it was the work of a well-coordinated group of German agitators. This theory fed into, or was fed by, the red scare active at that time.

The belief was that these agitators, perhaps with the help of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), used carefully trained “black Bolsheviks” to incite their brethren to riotous provocation. In spite of much federal money and personnel spent to investigate this theory, it was never substantiated (Kornweibel).

A similar but alternate theory popular with the government was that the IWW or organized labor was behind the activity. The theories varied, depending on the local politics.

In many areas of the North, industries had encouraged black migration as a source of cheap labor and, when necessary, these industries used nonunionized blacks as strikebreakers. In such a setting, the theory was common that organized labor was coordinating and inciting the white mob violence to frighten or stymie the effectiveness of the black strikebreakers.

The converse theory was found in communities where the white workers were not unionized, and the belief was that the IWW was motivating an insurgent black community to fight back against the white mobs. Authorities were never able to substantiate any of the theories.

The American Protective League (APL) is implicated by another theory. The APL was a national volunteer organization with the informal imprimatur of the federal government. It served a watchdog role in the United States during World War I.

These local bands of white men, full of nationalistic fervor, would watch the skies for German bombers and turn in their neighbors for any gesture deemed anti-American. They did work for the government, on a volunteer basis, that government agencies would not have been able to do either for lack of personnel and other resources or for issues of accountability.

APL records document many incidents of accusation and investigation, with some cases ending up in trial and jail time for citizens who had committed such “offenses” as speaking German, having too much sugar, or refusing to buy Liberty Bonds.

The APL enjoyed an unusual status, for while it was funded by contributions from corporations and businesses, it had the explicit logistical support and guidance of the Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the FBI) (Jensen). Once the war was over, however, the federal government insisted the organization disband, and it appeared to do so, although very reluctantly.

In many of the locations of red summer white-mob violence, there had been active APL chapters, and because the people participating in these mobs were often of the same demographic composition and nationalistic temperament as those who had formerly been American Protective League members, a case has been made that a causal relationship exists, but research into this theory is scant.

Records of individuals’ participation in mob action is virtually nonexistent, even in cases where a murder trial or other court cases followed, so a definitive link between any individual’s membership in the APL and participation in a red summer riot is elusive.

“Bossism” is the cornerstone of another conspiracy theory encircling some of the red summer riots, particularly the ones in Chicago, Omaha, and Longview. This theory holds that the force behind a riot was a political “boss” who bribed, paid, or otherwise motivated a band of agitators to lead a malleable mob to racial violence.

For decades in Omaha, for example, a powerful boss, Tom Dennison, controlled the mayoral office, and through it, the rest of the city, before and after, but not during, the year 1919. In October of that year, in the waning days of the red summer, a white mob burned down the brand-new courthouse and fought the sheriff’s department to take a black man, accused of assaulting a white woman, from the jail.

The crowd hanged the man and burned his corpse. When the mayor had tried to stop them, they tried to hang him, too. The theory is that Dennison had hired the men who incited the mob’s violence, in order to kill, or at the very least discredit, the mayor.

While this theory has not been proved or disproved, the following year a Dennison man was elected mayor. The federal government investigating this incident was unable to support its own theory that the IWW was behind the riot.

In attempting to explain a cause for the riots in 1919, the general practice of the authorities seemed to be to look first at the black people involved. If they had fought back at the white mob, the cause of the riot was believed to be black Bolsheviks or the IWW.

If the black people had not fought back against their attackers, or were grievously outnumbered or outfought, the blame was put on organized labor or German agitators. For the most part, the riots were not investigated thoroughly, and this is certainly true of the phenomenon as a whole.

An exception to this is the Chicago riot, for which the Chicago Commission on Race Relations was formed and assigned to investigate. The commission did publish an extensive study of the incident and the factors leading up to it.

Also, at the time of the riots, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) did at great risk send its own investigators to some of the riot locations to interview people and report back. In the years since the red summer, the Chicago riot, the Knoxville riot, and the violence in Elaine, Arkansas, have been the most studied by scholars.

The violence of the red summer abated gradually as winter arrived in 1919, and while lynching was not completely stopped for a number of years, and isolated rioting occurred sporadically throughout the rest of the century, there has not been another such epidemic of rioting since.

While the various conspiracy theories associated with the red summer have never been proved or disproved, the generally accepted analysis, for now, is that an overall climate of instability and unrest allowed tensions of various types, based in local issues, to manifest in patterns of extreme group violence.