|

| Sinking of Lusitania |

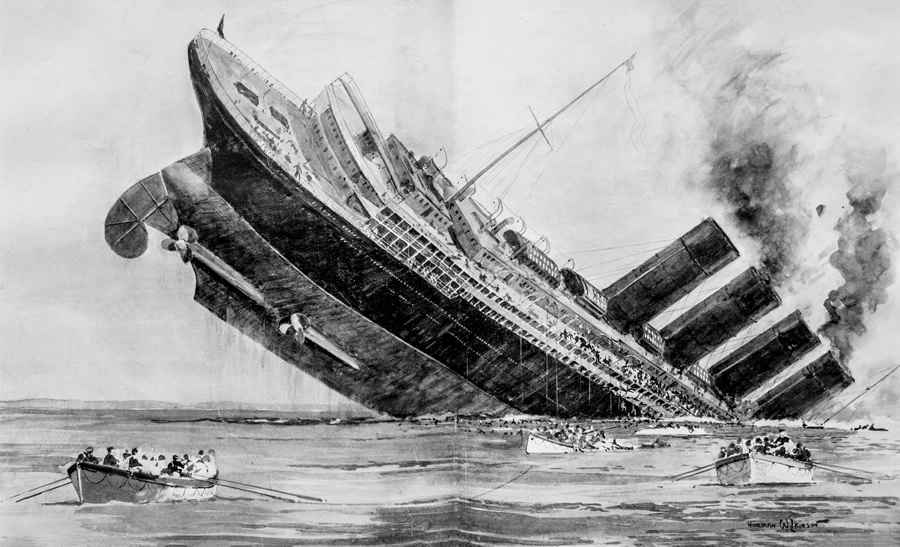

The Cunard passenger liner the Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat on 7 May 1915 off the south coast of Ireland, en route from New York to Liverpool, resulting in the loss of 1,200 lives, 128 of them American.

Allegations of a conspiracy to sink the Lusitania center upon the claim that the then First Lord of the British Admiralty, Winston Churchill, colluded with the First Sea Lord, Admiral Jack Fisher, and other senior leaders of the Royal Navy, to place the liner in peril, anticipating that heavy loss of U.S. lives would hasten the intervention of the United States in World War I.

While it is accepted that part of the Lusitania’s cargo comprised munitions for the Allied war effort, there have also been suggestions of a conspiracy to conceal both the precise nature of these war supplies and the military capacity of the ship itself.

|

The emergence of a conspiracy to sink the Lusitania is usually traced to a conference hosted by the British Admiralty in Whitehall on 5 May, two days before the liner was sunk, where a decision was made to withdraw the Lusitania’s naval escort without notifying the ship, in waters where U-boats were known to be active.

Among others summoned to attend the meeting was Joseph M. Kenworthy, a lieutenant commander who worked for naval intelligence, and whose only prior association with Churchill had been when Kenworthy submitted a report, commissioned by Churchill, assessing the political outcomes should a passenger liner carrying American citizens be attacked and sunk by the German navy.

But the suggestion that Churchill and other senior members of the admiralty conspired to sink the Lusitania is problematic. Records from the admiralty conference on 5 May indicate that British naval forces stationed in Ireland were instructed to protect the ship. It is also a matter of record that at least eight, and possibly more, warnings of U-boat activity off southern Ireland were communicated to the Lusitania on 6 and 7 May.

Notwithstanding the urgency of these warnings, and the admiralty’s awareness of the U-boat threat, a more prosaic explanation for why the liner found itself unguarded in dangerous waters may lie in the complacency of the British military. In April 1915 Churchill had written that Britain “enjoyed a supremacy at sea the like of which had never been seen even in the days of Nelson.”

Assured, they assumed, of naval supremacy, and with their attention focused on the ongoing campaign in the Dardanelles, the men responsible for British naval policy may simply have paid insufficient attention to the dangers of U-boat activity closer to home. The notional desertion of Lusitania by her naval escort the Juno has been described, even by those who see a conspiracy, as following the standard pattern for rotation of patrol ships in the area.

Secret Military Cargo

Suspicions regarding the exact nature of the Lusitania’s cargo have been aroused by discrepancies in the two separate cargo manifests Cunard lodged with U.S. customs, one before and one after the ship’s departure from New York.

Yet, in order to keep cargoes secret from German informers operating on the New York docks, it was standard practice for British shipping companies during World War I to file conflicting or incomplete manifests before sailing, and nobody has yet demonstrated convincingly that Cunard actively misled either the U.S. authorities or the public as to the contents of the ship’s hold. The day after the Lusitania was torpedoed, for example, the New York Times published full details of the liner’s military cargo in its edition of 8 May.

The civilian status of the Lusitania has also been challenged, with allegations that the liner carried a hidden arsenal that could be rapidly mobilized for use as necessary. A conspiracy to conceal the Lusitania’s military capacity has even been linked with the unidentified relative of an unidentified future U.S. president. But none of the 109 passengers who eventually testified at the two public inquiries into the disaster recalled seeing guns mounted on the liner.

More intriguing is the debate about what caused the fateful “second explosion” on board the ship. Although the admiralty maintained for some years that U-boat U-20 had hit the ship with two torpedoes, it is now widely accepted that the submarine fired only one torpedo at the Lusitania, and that the second catastrophic detonation, the one that sank the liner so quickly with such huge loss of life, was caused by an unknown object or substance the ship was carrying in its cargo.

The second explosion has been explained in a number of ways, ranging from the lurid (the Lusitania was carrying a cargo of secret explosive powder) to the banal (the ship was sunk by a detonation of highly flammable coal dust following the impact of the torpedo).

But no comprehensive explanation for the second explosion has ever been offered, and the admiralty’s initial insistence on the “two torpedo” scenario has kept alive the theory of a high-level cover-up regarding the contents of the Lusitania’s holds.

As well as the cause of the second explosion, one further aspect of the Lusitania conspiracy remains unresolved. In the aftermath of the sinking, early accounts estimated that the liner had taken to the bottom of the sea several thousand dollars in cash. By 1922 these estimates had been revised, with some commentators valuing the ship’s cargo at $5–6 million, much of it in gold.

During the 1950s the activities of the salvage company Rizdon Beezley around the wreck revived suspicions of Churchill’s involvement in the disaster, with allegations that Churchill had commissioned the company to remove evidence of contraband from the wreck. To this day, no convincing explanation has been offered as to why the Lusitania would have been carrying millions of dollars of gold into a war zone.