|

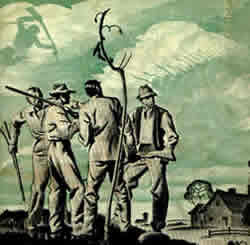

| The Green Corn Rebellion |

Although signs of the conspiracy were discovered in various parts of Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas, overt acts of violence were confined to approximately 6,000 square miles, and the majority in half that area in the four contiguous Oklahoma counties of Seminole, Pottawatomie, Hughes, and Pontotoc.

Agitators from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Working Class Union (WCU), the Socialist Party, the Jones Family (the poor people’s secret name for their organization), and Catholic baiters convinced the farmers that at least 2 million others were mobilized, more would join the cause as they marched east, and the whole nation would rise up in arms.

They called meetings in the woods, as many as three per week, and promised the farmers two carloads of rifles. They argued that they shouldn’t be fighting farmers and workers in Germany, when the real enemies were the capitalists at home.

|

But it did not take much convincing. Many of the farmers were suffering from poor soil, from uncontrollable costs of production, transportation, and storage, from bad weather and insect infestation, and from an uncertain market. They also saw those with whom they dealt, the banker and the smalltown merchant, as highly prosperous.

H. H. Rube Munson, a paid IWW organizer, came to the area to stir up resistance to the draft. Another IWW professional, J. E. Wiggins, revived the dormant, indigenous Working Class Union and built upon the strength of the Socialist Party in the area. He combined socialism and anarchism to foment draft resistance and inflated the group’s feeling of strength by numbering membership cards in the millions, and holding meetings in secret.

But only isolated incidents occurred. Rebels dynamited the Dewar waterworks on 7 June, resulting in the arrests of nine WCU members, cut the livestock fences owned by some banks, pulled down communication lines in Francis and a few other places, partially burned four bridges, attempted to blow up the storage tanks of the Magnolia Petroleum Company in McAlester, threatened to destroy the McAlester Grain and Elevator Plant, and stole property of some of the wealthy.

The IWW set 2 July for the grand mobilization, but when the day arrived it was postponed to 3 August. On 2 August a party of five black WCU members ambushed Sheriff Frank Grall and his deputy, J. W. Cross, in Little River country, south of Seminole.

After wounding Deputy Cross, the farmers fled. That same night a band of rebels marched from farm to farm soliciting recruits and camped on a sandbar in the South Canadian River. The next morning part of the group tried to destroy the railroad bridge over the river.

About a hundred others, under command of Captain Bill of the Red Sash, moved to a bluff on Old Man Spear’s farm, where the owner ran up a red flag in his backyard and denounced “Big Slick,” President Woodrow Wilson, for getting the country into war. When a twenty-five-man posse approached the bluff the rebels ran into the woods.

The next day nearly 1,000 posse men from seven counties began the final campaign. Three rebels were killed, 400 arrested, and 120 indicted for seditious conspiracy and conspiring to obstruct the Selective Service Act. Three were sentenced to ten years in prison, two to six years, and a number from one to four years; 154 pleaded guilty to draft resistance. During the trials authorities set exorbitant bails and systematically excluded socialists from juries.

The eastern press portrayed the farmers as perpetual renegades who merely used the draft as a pretext to resist the government. It did not understand the economic plight of the farmers, their real concern that conscription would lead to their death in Europe, and their traditional honesty and law-abiding nature.