A popular armed uprising in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1841, the Dorr War sought to extend the restricted suffrage of the state constitution. Although some conspiracy-minded historians have argued that Tammany Hall, the New York Democratic Club, was responsible for the Dorr War or manipulated unrest over suffrage in Rhode Island to gain partisan advantage, it appears that Tammany did not enter the picture until late in the dispute and gained very little from it.

Reformers had protested for years about the right to vote being limited to property owners. By 1840 a majority of adult males no longer owned real estate in Rhode Island, but many did possess a significant amount of personal property.

Suffrage requirements were contained in the royal charter granted by King Charles II in 1663, which became Rhode Island’s constitution in 1776. The charter also apportioned representation on the distribution of population as it was in 1663, so that as people moved from rural areas to the cities, urban dwellers became vastly underrepresented.

|

In 1811 the Rhode Island Senate with a Republican majority passed a bill to extend the suffrage, but the Federalists in the House defeated it. Popular agitation began with a mass meeting in Providence in 1820, and the legislature responded by putting the suffrage question to a vote of the people.

But with only property owners voting, it lost 1,600 to 1,900. In 1825, when a convention to rewrite the state constitution considered extending the suffrage, only three delegates voted for it. Then, qualified landowners voted against ratifying the proposal, which contained a reapportionment.

Four years later, 2,000 persons appealed to the legislature to extend the suffrage, but the House reported that landholders were “the only sound part of the community.” They argued that if the landless did not like it, they should acquire real property or move elsewhere. In 1832 more petitions met the same fate.

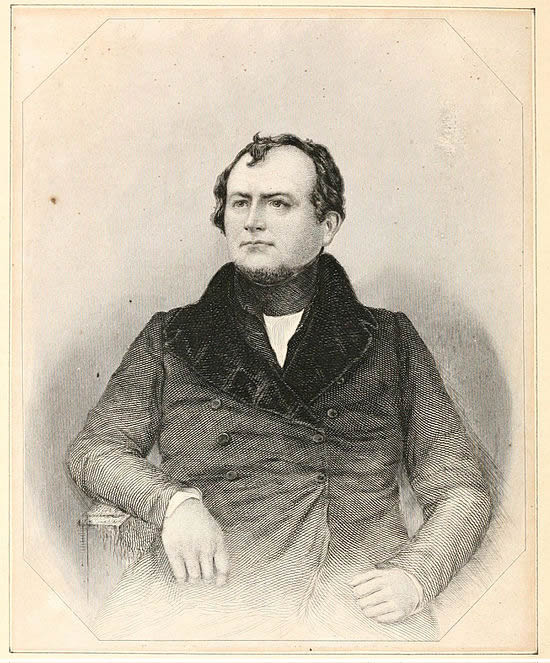

Growing dissatisfaction manifested itself in the formation of the Constitutional Party at a meeting of representatives from ten communities on 22 February 1834 in Providence. The next month twenty-nine-year-old attorney Thomas Wilson Dorr, Harvard class of 1823, addressed another meeting of delegates from twelve towns. When only 700 persons voted for its candidates in 1837, the party disbanded.

Then, in the autumn of 1840, Dr. J. A. Brown organized an anti-Whig group called the Rhode Island Suffrage Association, which spread to every town in the state. It published a paper called the New Age, held mass meetings characterized by lively speeches, wore badges, waved banners, and paraded with a band.

When the legislature rebuffed the people’s petitions, the association called for a People’s Day on 17 April 1840. Three thousand attended the demonstration in Providence and adjourned to Newport the next day, where delegates appointed a committee to call a People’s Constitutional Convention, and paraded through town, several carrying guns.

Events moved rapidly. On 28 August 1841, 7,512 people voted for delegates to the People’s Convention, which drafted a constitution on 4 October. They revised it on 16 November and called for its ratification. From 27–29 December, 13,944 people voted for, 52 against. The People’s candidate for governor was the same dedicated and obstinate Thomas Dorr, who had addressed the Constitutional Party meeting in 1834.

He was the son of an aristocratic Woonsocket manufacturer, a respected member of the community, a onetime Federalist, an anti-Jackson Whig, a pro–Van Buren Democrat, president of the Providence School Committee, treasurer of the Rhode Island Historical Society, and representative in the state legislature. On 18 April 1842, 6,359 people voted for him to lead a new People’s government.

But the charter authorities were not idle. They opposed what they considered a usurpation of authority and provided severe penalties for those who ran for office or voted in the People’s election. To prevent his being arrested, Dorr called for an armed escort on inauguration day, 3 May. According to the Providence Daily Journal, 3,000 people marched in the inaugural parade, approximately 850 under arms. The next day the charter government declared Rhode Island in a state of insurrection.

On 17 May Dorr and seventy armed volunteers forced a six-man, sword-armed guard to surrender the Armory of the United Train of Artillery and captured two six-pound cannons. By 1:00 A.M. the next day Dorr’s troops dwindled to 250 men. They approached the Providence Arsenal in a fog under a flag of truce, and Dorr demanded the Arsenal surrender.

From his well-fortified position with an overwhelming force Colonel Blodgett refused, but held his fire. Dorr lit the fuses on his cannon. There was a flash of powder in the pan, but no report and Dorr and his troops slipped away in the early morning fog. The next day he escaped to Connecticut. He tried to establish his government again and met the same opposition.

The only fatality in Dorr’s War occurred on 27 June. In Chepachet, a group of brick-throwing Dorr sympathizers from Massachusetts assailed the Kentish Guard at the Pawtucket Bridge. When the crowd failed to disperse, the Guard volleyed over their heads. The crowd continued to throw bricks and the Guard fired into the crowd, killing one man.

On 21 June 1842, the state legislature called a constitutional convention with delegates apportioned on the basis of the 1840 census. The convention drafted articles extending the suffrage and redistricting the legislature, and the people ratified the new document, ending the longtime struggle.

Both sides appealed to the national government for assistance, but all three branches demurred. President John Tyler refused to send troops, the Senate tabled a resolution requiring the president to inform Congress of his actions, and Chief Justice Roger Taney, speaking for the Supreme Court in an 8–1 decision involving a dispute over which government was the proper authority, wrote:

“No one, we believe, has ever doubted the proposition, that, according to the institutions of this country, the sovereignty in every State resides in the people of the State, and that they may alter and change their form of government at their own pleasure.

But whether they have changed it or not by abolishing an old government, and establishing a new one in its place, is a question to be settled by the political power. And when that power has decided, the courts are bound to take notice of its decision, and to follow it” (Luther v. Borden).

When Dorr returned to Providence in October 1843, after being celebrated by Tammany Hall in New York, the government arrested him at the City Hotel, tried him before the state Supreme Court, and convicted and sentenced him to life in prison. The legislature released him on 27 June 1845, restored his civil rights in May 1851, and pardoned him in January 1854. He died a year later at age forty-nine.