|

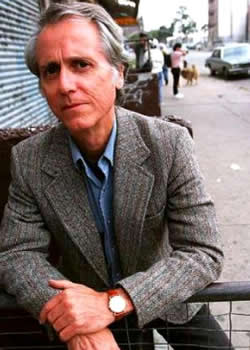

| Don DeLillo |

Don DeLillo, the distinguished contemporary U.S. novelist, is the author of thirteen novels—including Amazons (1980), a pseudonymously penned novel by Cleo Birdwell—and two plays. His many awards include the National Book Award for White Noise (1985), the PEN/Faulkner award for Mao II (1991), and in 2000, the William Dean Howells Medal for Underworld (1997).

DeLillo is also the first American to receive the Jerusalem Prize (1999) in recognition of his complete works that, in the words of the prize committee, “express the theme of the freedom of the individual in society” (Time).

DeLillo’s novels are prescient critiques of U.S. culture, engaging specifically U.S. subjects like cultural materialism, sports hysteria, rock music, terror and violence, conspiracies, waste, post–World War II U.S. history, corporate America, and the assassination of John F. Kennedy. DeLillo’s works are prophetic as they apprehend and explore latent U.S. ills before they achieve privileged status in the media.

DeLillo understands that many U.S. predilections are connected as Underworld claims: “everything is connected in the end” (826). For his acute perceptions DeLillo has been dismissed by the New York Times Review of Books as the “chief shaman of the paranoid school of American fiction” (Begley, 303), and detractors criticize him for his tenacious exhuming of Americana and for creating what Bruce Bawer calls, “conspiracy-happy protagonists” (35).

|

Speaking with Anthony DeCurtis on the Zapruder film, DeLillo remarked that “the strongest feeling I took away from that moment is the feeling that the shot came from the front and not from the rear” (291). From this comment, and its implication of an alternative to the Warren Commission’s findings, critics immediately branded him as a conspiracy theorist writing fiction. It is not surprising that DeLillo’s artistic integrity has invited such criticism.

DeLillo’s work is perhaps better understood as daring, exploring the underside or undercurrent of U.S. history and culture. DeLillo’s significance emerges from his willingness to explore alternatives to the mainstream consensus and to address the unaccountability of the many, intricate connections— cosmic, quotidian, and profound—of chance and coincidence in modern and contemporary America.

Much of DeLillo’s writing underscores what he calls in his first novel, Americana (1971), the “true power of the image” (12), particularly media images. For DeLillo, no image is more penetrating and culture-altering than frame 313 of the Zapruder film, the frame capturing the precise moment of Kennedy’s assassination.

The assassination is so pervasive in U.S. culture and so significant for DeLillo that he has asserted in an interview with Adam Begley that U.S. history seems “engineered” since then (303), and that it even “invented” him as a writer (DeCurtis, 285). This is not to say that DeLillo views history as necessarily controlled as part of a massive military-industrial conspiracy, but that he has charted a collective shift in U.S. consciousness since 22 November 1963.

Moreover, a corollary of DeLillo’s works is that they call for a more critical appraisal of our cultural media images by pointing to and critiquing prominent images, like the famous picture of Lee Harvey Oswald holding a Manilicher rifle and purportedly Communist journals. It has been alleged that the photo was adulterated with Oswald’s head inserted afterward.

Don DeLillo has found resonance and connectivity in parallel U.S. events since JFK. He has further tailored his fiction for, and written perspicacious essays on, seemingly disparate events like Oswald’s death (Libra), shot simultaneously by television cameras and Jack Ruby’s pistol, and the Ronald Reagan assassination attempt with, as he writes in “American Blood,” its “choreography of gesture” of Secret Service agents flourishing drawn weapons (24).

Don DeLillo here shrewdly notes that Americans are so culturally steeped in the lore of JFK’s assassination that even Reagan’s agents displayed a palpably self-conscious awareness of the gravity of their videotaped moment as the drama unfolded, and that event’s historical antecedence in JFK’s assassination. In an age of ubiquitous video cameras and amateur-video footage, Don DeLillo contends that it is no longer possible to live without an urgent selfconscious awareness, even during the mundane happenings of common existence.

For DeLillo, the United States unalterably changed in 5.6 seconds at Dallas’s Dealey Plaza. Connecting subsequent events with the Kennedy assassination is not paranoid, as DeLillo’s detractors have claimed. Rather, it demonstrates a circumspect understanding of the power of U.S. media images, and how no event after JFK can be performed without reference to the assassination on some level.

His work often returns to doublings and mirrored events. In Libra, Lee Harvey Oswald and Kennedy’s lives are linked; DeLillo himself claims an affinity for Lee Harvey Oswald, noting that they lived close to each other as children in the Bronx. The basis for DeLillo’s largest and perhaps most complex novel, Underworld, is the 4 October 1951 New York Times’ double headline of “Giants capture pennant” and “Soviets explode atomic bomb.”

The headlines’ interpenetrating “shot-heard-around-the-world” resonance and synchronicity is just one of many chance events of twentieth-century America that engage Don DeLillo. For Don DeLillo, our age is increasingly technologically bounded, and while these gains are beneficial they are also bewildering and isolating. DeLillo’s fiction, then, operates as a counter to U.S. existential loneliness and despair.

His fiction is a restorative by turning our collective attention back to the ordinary elements of human life, noting the sometimes alarming moments of conjunction in disparate episodes. Finding these instances of revelation and transcendence in seemingly typical junctures is a hallmark of his fiction.