|

| Lee Harvey Oswald |

Lee Harvey Oswald (1939–1963) has been U.S. “Public Enemy #1” ever since his posthumous conviction in the court of popular opinion for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. For most people, his supposed acts in Dallas on 22 November 1963 remain the single most memorable event of Oswald’s short life.

Nevertheless, the facts and enigmas of his twenty-four years have inspired as much scholarly debate and public controversy as any number of longer-lived, more colorful and influential U.S. antiheroes such as J. Edgar Hoover, Jimmy Hoffa, or Richard Nixon.

To this day, there is no firm consensus regarding his actions in those fateful hours or the circumstances leading to them, although in recent years the balance of popular and scholarly opinion has begun to favor the theory that he was involved—perhaps unwittingly—in some kind of conspiracy to assassinate the president.

From Communist Novice to U.S. Marine

|

Born on 18 November 1939 in a downtrodden neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, Oswald had a family life that was, by any standards, unsettled. Although his father’s early death meant that Lee’s childhood was, like that of many youngsters born during the war, dominated by his mother, it is fair to say that Marguerite Oswald

A succession of relationships and family connections with figures on the fringes of organized crime have proven fertile ground for conspiracy researchers like Anthony Summers

By the age of sixteen, already a frequent truant and briefly an inmate of the Bronx’s Youth House correctional institute, Oswald had begun to describe himself as a Communist. He claimed to have been won over to the beleaguered U.S. Left by the plight of the Rosenbergs, whose ongoing court case brought about a short-lived revival of the Communist Party’s fortunes in the early 1950s.

From his own fascinating but still unpublished writings, and the hundreds of pages of testimony given during the official inquiry into Kennedy’s death, the picture emerges of a hostile, potentially violent and impressionable youngster who was inflamed by the lurid rhetoric of the Left and turned to the uncompromising radicalism of the Communist movement at the height of McCarthyism.

Borne out by contemporary school reports, and lent credence by the careers of other leftists and political assassins like Leon Czolgosz

However, the interpretation of Oswald as a loner has not convinced everyone. In some accounts he emerges as a typical teenager, prone to scrapping with his peers and voicing extreme opinions maybe, but hardly a callous agent of U.S. communism steeling himself for a final conflict with the U.S. establishment.

For one thing, Oswald never actually joined either the Communist Party (CPUSA) or any of the other leftist groups like the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) with whom he frequently corresponded. Even more significant, in 1956, having left school the previous year, he enlisted with that bastion of U.S. neoimperialism, the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC).

Early scores from aptitude tests and other assessments of his conduct and proficiency taken during his military service all reveal a slightly below-average performer. For obvious reasons, his ability with a rifle has long been the subject of fierce controversy on which the most that can be said with any certainty is that, while not an exceptional marksman, he was far from the worst in his unit.

That he could have accomplished the fatal, once-in-a-lifetime result in Dealey Plaza was asserted first by the Warren Commission following lengthy ballistics tests, and is a conclusion recently bolstered by computer assessments performed for Gerald Posner’s 1993 book, Case Closed.

For many other authors, however, the extraordinary, almost superhuman performance Oswald would have needed to achieve on the day, together with analysis of the wounds on the president’s body, is enough in itself to imply the presence of a much larger team of gunmen installed in various positions around the Plaza, and therefore, by definition, a conspiratorial interpretation of the event.

Certainly, Oswald’s military career was unorthodox, and this period has been subjected to increasing scrutiny by conspiracy theorists. He seems to have made no secret of his Marxist leanings and indeed continued to learn Russian and subscribe to Pravda, facts that undoubtedly marked him out as highly suspect among fellow marines in the midst of the cold war.

No less anomalous were his bizarre assignations with members of the local leftist and criminal underworld while on maneuvers in the South China Sea. For Edward Epstein, one of the pioneers of Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory, these mysterious connections, coupled with his training in sensitive radar-control techniques as part of the U-2 spy plane program, point toward the presence of intelligence communities on one side or other of the Iron Curtain influencing his actions.

Recently, following Epstein, other writers, including Anthony Summers and former army intelligence officer John Newman, have explored the possibility that Oswald may have been recruited by U.S. military intelligence to work as a “deep cover” agent in the Soviet Union.

This is one of the theories dramatized in Oliver Stone’s controversial movie JFK (1992), itself based on the writings of Jim Garrison and Jim Marrs, and it certainly provides a plausible explanation for the wealth of unanswered questions in the standard narrative of Oswald’s military service established by the Warren Commission.

Oswald’s Russian Years

In spite of their suspicions of his left-wing interests and tendencies, few of Oswald’s fellow marines could have predicted his dramatic next move. In the summer of 1959, after his discharge from the USMC, Oswald began to set in train a complicated plan that would result in his defection to and residence in the then Soviet Union. This act—impressive in itself given his youth—has, like every other aspect of his life, been scrutinized for evidence of the hidden hand of possible agents of conspiracy.

And for good reason: on 31 October 1959, he presented himself to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, saying that not only did he wish to renounce his American citizenship, but that he also planned to furnish Soviet intelligence with the military secrets he had learned during his training in the U-2 program.

After several months of unhappy isolation in the Metropole Hotel in Moscow, during which he met future biographer and suspected CIA agent—Priscilla McMillan, and even attempted suicide, Oswald was finally sent on a “Stateless Persons Identity Document” to the industrial city of Minsk, in the province of Belorussia.

That Minsk was located near an espionage training school, and that he was supported by a Soviet government allowance that amounted to a small fortune in the Soviet Union, has led some commentators to speculate that he may indeed have passed intelligence to his hosts, in return for which he was given the “red carpet” treatment.

In any event, Oswald would remain in the Soviet Union for around three years, working in the Belorussian radio and television factory and socializing with some decidedly suspicious members of Minsk society.

When, in April 1961, he married a young student named Marina Prusakova

Certainly, the couple’s every conversation in their relatively luxurious apartment overlooking the Svisloch River was now recorded and monitored by local KGB agents. Whether or not this was because Oswald represented a valuable intelligence source and potential agent or was merely an asset in the cold war diplomatic chess game remains unclear.

However, the balance of evidence from sources such as the frequently unreliable Soviet defector Yuri Nosenko

In spite of the circumstances of his defection, Oswald soon grew disillusioned with life in the Soviet Union. To judge from the large and compelling body of essays, diaries, and letters he produced during his time in Minsk, it is clear that, like many other ideological defectors, he was most distressed by the gap between Communist rhetoric and Soviet realities, and by the regimented, repressive conditions inside Khrushchev’s empire.

In fact, at around the same time as he met Marina, Oswald had reopened negotiations with the U.S. Embassy. There followed well over a year of diplomatic wrangling, including several dangerous, illegal visits to Moscow and hostile KGB interrogations of his wife.

|

| Lee Harvey Oswald with his wife, Marina, and their son, June |

Finally, early in 1962, Lee secured exit visas for himself and his family. For some conspiracy critics like Anthony Summers and Jim Marrs, the progress of the Oswalds’ return to the United States appears to have been far too smooth, especially given Lee’s record of anti-American statements and actions.

Likewise, the departure of Marina and their baby daughter June seems to have been achieved with a striking lack of the usual Soviet bureaucratic obstruction. Having said all that, according to some of Posner’s and Mailer’s intelligence sources, the Soviets may simply have been glad to see the back of this troublesome family.

On balance, it seems that, just like in the United States during his teenage years, Oswald had proved unable to keep his criticism of the Soviet regime to himself and had made many powerful enemies in the Soviet Union.

Oswald the New Leftist?

Oswald spent his last eighteen months in the southern cities of New Orleans and Dallas. During this period, according to the story established by the Warren Commission, he gave every sign of seeking to create for himself a reputation as a dynamic and forceful radical.

In these months, he was in regular contact with several of the remaining parties of the U.S. Left, including the CPUSA and the SWP, as well as parties of the “New Left” such as the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), which, due to the rise of Fidel Castro’s socialist regime, could claim scores of powerful supporters in the early 1960s.

In addition to the various series of correspondence between Oswald and the leaders of these parties, many of which are contained among the Hearings and Exhibits of the Warren Commission and make fascinating reading, there are also several texts— apparently written for his wife in the event of his imprisonment—in which Oswald apparently seeks to justify an assassination attempt on Major General Edwin Walker.

As one of the South’s most aggressive segregationists and John Birch Society leaders—and, ironically, an enemy of Attorney General Robert Kennedy—Walker was certainly a natural target for a leftist, especially one like Oswald, who is remembered at this time as being an outspoken advocate of desegregation.

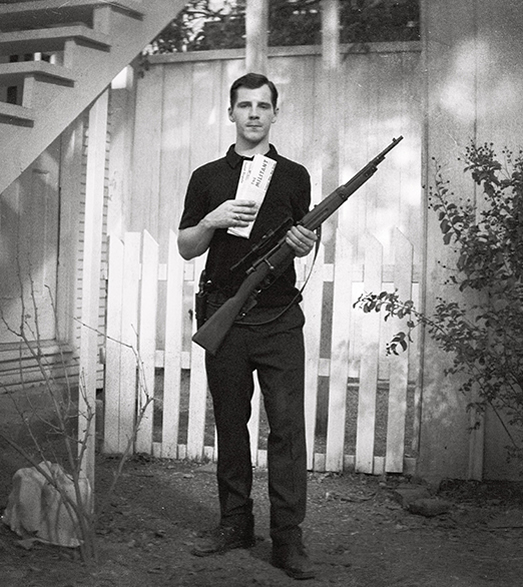

That Oswald confessed to his wife and others to having taken a shot at the general in April 1963 was, for obvious reasons, seized upon by the Warren Commission as evidence of an existing propensity to act out his leftist beliefs in a violent and potentially murderous way.

And yet, as with every other event in his life, the circumstances of Oswald’s attempt on Walker’s life become more mysterious the more scrutiny is paid them. Indeed, in these confusing last months, Oswald’s actions seem to have become even less comprehensible and more subject to debate.

As the House Select Committee on Assassinations found during their reinvestigation of the case in the late 1970s, there is evidence to suggest that Oswald was not alone outside Walker’s house on the night of the shooting, and that he may well have attended several of the right-wing extremist’s rallies and meetings in the months thereafter.

Such suspicions, fleshed out by later conspiracy critics like Anthony Summers, raise the contentious but central question of the nature of Oswald’s political affiliations, and how they may have run contrary to his stated opinions at this time.

If relations with his wife abruptly deteriorated after their arrival in the United States, then Oswald was certainly consorting with a bizarre cast of radicals and activists of both Left and Right. One of these obscure figures was George de Mohrenshildt, a shadowy Russian exile and flamboyant businessman with provocative connections in the worlds of U.S. intelligence and organized crime in the United States and Latin America.

According to Norman Mailer’s account of the strange friendship that developed between the two men, de Mohrenshildt was most likely a CIA contract agent charged with the task of debriefing Oswald about his experiences behind the Iron Curtain. However, this may well have been only half the story.

For Peter Dale Scott

Certainly, there was more to Oswald’s relationship with de Mohrenshildt than the Warren Commission were prepared to concede in their report, in spite of the unsettling evidence to the contrary that they suppressed when it was published in 1964.

Much of this evidence, and indeed the most continually perplexing aspect of Oswald’s life as a whole, concerns his involvement in the complicated politics of Cuban-American relations throughout his last eighteen months.

On the face of it, the stories of Oswald single-handedly establishing a cell of the FPCC in the hostile environs of New Orleans would seem in keeping with the Warren Commission’s narrative of a radical activist growing increasingly dissatisfied with the parties of the Old Left, and searching for an alternative model in the politics of Third World revolution.

Certainly someone, if not Oswald himself, seems to have been careful to create a convincing paper trail indicating the presence of such a figure, including extensive correspondence with Vincent Lee, then general secretary of the FPCC, appearances in the New Orleans news media, and even a trip to Mexico City, ostensibly to present himself as a potential defector to the Cuban Embassy.

And yet now, after many years of research into just this aspect of the case, there exists a substantial body of evidence to suggest that Oswald’s connections and activities at this time were far less straight-forward. For one thing, according to many accounts, he appears to have been in contact with both proand anti-Castro forces massing in New Orleans and other cities in 1962–1963.

While he undoubtedly was in touch with members of the FPCC and other groups, it also appears that Oswald was working—perhaps as a double agent—with a much larger group of anti-Castro Cuban exiles then being coordinated by the CIA and financed by their allies in the national organized-crime network.

It is for this reason that his name has been plausibly linked with a range of key players in the underground world of deep politics, including Mafia generals and footmen such as Santos Trafficante, Sam Giancana, John Roselli, and his own future killer Jack Ruby; rogue CIA contract agents like George de Mohrenshildt, David Ferrie, and Guy Bannister; and renowned local Cuban exile leaders like Carlos Bringuier and Antonio Veciana, who had links with both.

Although they characteristically use these various suspicious connections as a way of exploring the much larger question of the possible nature of a JFK assassination conspiracy rather than clarifying Oswald’s precise role in such a conspiracy, the work of authors such as Anthony Summers, Peter Dale Scott, and Jim Marrs has served to debunk the Warren Commission’s central conclusion that Oswald acted throughout his life as a “lone agent.”

Oswald’s Death

Oswald’s own death, no less than that of President Kennedy, remains shrouded in mystery. According to the official record of marathon interrogation sessions conducted by the combined forces of the Dallas Police Department, FBI, and the Secret Service between 22 and 24 November 1963, Oswald was initially arrested for the shooting of Patrolman J. D. Tippit during his supposed getaway dash from Dealey Plaza.

Within twelve hours, he had also been charged with President Kennedy’s murder. In all that time, he remained unrepresented by legal counsel, in spite of repeated calls to renowned left-wing lawyer John Abt.

If the legal profession apparently distanced itself from Oswald, the international press corps were an almost constant presence; according to one contemporary estimate, over 300 representatives of the news media descended on the Dallas Police Department, creating a media circus.

In a remarkably short time, a detailed account of Oswald’s defection and leftist career had emerged, presumably from the FBI, who had long maintained a file on him, and had been fed to the waiting press.

Oswald’s “fifteen minutes of fame” came to an abrupt end, however, on the morning of Sunday, 24 November, when, en route to Captain J. Will Fritz’s office for a further round of questioning, he was shot dead by local club-owner and small-time mafioso Jack Ruby.

|

| Ruby about to shoot Oswald who is being escorted by Dallas police. |

Ever since his death, there have been many who have maintained that the official record of that dark and chaotic weekend was woefully inadequate. For some, Ruby’s sudden appearance among the police officials and newsmen at precisely the moment Oswald emerged from his temporary jail cell leaves the strong suspicion that the killer was forewarned by someone on the inside.

This has led some authors to explore Ruby’s links with corrupt elements within the Dallas law-enforcement community. No less significant is the possibility that Oswald may have known both Tippit, whose involvement in several right-wing enclaves has long been suspected, and Jack Ruby.

For the 1979 Assassinations Committee, such suspicions aligned with their conclusion that, if there was a conspiracy to kill the president, it was undoubtedly instigated by the Mafia in collaboration with extreme right-wing elements, both of which would have had a vested interest in silencing Oswald soon after his arraignment for the murder.

Oswald’s Disputed Legacy

In the forty years since his death, Oswald’s reputation and the meaning of his actions and possible affiliations have played a central role in our comprehension of the Kennedy assassination.

Over the years, he has been seen as an archetypal psychopath or “lone gunman” with delusions of political agency, and as a scapegoat or “patsy” for the larger machinations of secret, unaccountable branches of the socalled shadow government like the FBI, the CIA, and the Mafia.

Between those two extremes, Oswald was briefly reclaimed in the late 1960s by the Weathermen, a terrorist offshoot of the Black Panther Party, some of whose members cited him as a role model of direct action and carried his iconic image on their posters.

More recently, reflecting increasing interest in some of the CIA’s more esoteric operations, several writers have sought to explain Oswald’s paradoxical behavior and radical shifts of allegiance as evincing the influence of covert mind-control and “parapsychological” experiments carried out by the CIA as part of the MK-ULTRA program.

Complementing the research of political and social historians, Oswald’s singular odyssey has also inspired some of the best work by major novelists such as Norman Mailer and Don DeLillo. In DeLillo’s Libra (1988), for instance, the specific nature of Oswald’s involvement in the assassination is left deliberately unresolved, his story told in dramatic counterpoint to the convoluted plans of rogue secret agents and political extremists.

On the other hand, in Mailer’s recent account, Oswald emerges as the culmination of that pantheon of lone agents like D.J. from Why Are We in Vietnam

Regardless of his culpability or otherwise in the murder of President Kennedy, the figure of the lone gunman, as much the product of the Warren Commission’s influential interpretation of them as of Oswald’s own actions, has become a recurrent character-type in popular media and literary fiction alike, from Robert DeNiro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (1976) to the villains of recent movies such as In the Line of Fire (1993), Speed (1994), and Seven (1996).