|

| Boston Tea Party |

British colonists saw the 16 December 1773 Boston Tea Party as justified resistance to a conspiracy that threatened their freedom. The relationship between the North American colonies and the British government had changed dramatically since its victory in the Seven Years’ War against France a decade earlier. The expense of maintaining a global empire had increased substantially.

Britain’s national debt nearly doubled during the war years and costs further escalated when the government decided to station regular troops in North America to protect its expanded territory. Facing growing resistance to taxation at home, British ministers, beginning with George Grenville, concluded that they must make the empire more efficient and raise revenue in the colonies.

Most colonists, however, interpreted efforts to enforce customs regulations and taxes like the Stamp Act and the Townshend duties as elements in a grand scheme to take away their rights. They demonstrated their concerns through petitions and publications, economic boycotts, and crowd actions, all of which led to the repeal of most of those taxes.

|

Background

The remaining tax was on tea, a commodity widely consumed in the colonies. However, many colonists drank smuggled tea imported from Dutch sources. This circumstance contributed heavily to a growing financial crisis facing the British East India Company.

In an effort to help the troubled company, raise revenue, and confirm Parliament’s right to tax the colonies, Prime Minister Frederick North gained passage of the Tea Act in May 1773. This law allowed the company to ship its tea directly to the colonies and consign the commodity to its own agents, reducing company costs. Although the tea continued to carry a tax of three pence per pound, the price would be less than that of smuggled tea.

Opposition to the Tea Act arose first in Philadelphia and New York, where merchants who had been smuggling tea faced a serious loss of business. They raised arguments that others soon incorporated into their conspiratorial analysis of British actions. The merchants contended that the monopoly given the East India Company for the distribution of tea would be a precedent for all foreign trade.

They also argued that the Tea Act was a sinister ploy to deceive the colonists into accepting the tea tax through a lower price for a favorite beverage. In response to threats of rough treatment from mass meetings and numerous widely circulated broadsides, tea consignees in Philadelphia and New York, as well as Charleston, South Carolina, resigned.

Boston radicals did not immediately respond because they were preoccupied with a scandal involving Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson. They had published some of the governor’s letters, revealing his belief in the need to abridge the colonists’ English liberties in certain circumstances. The letters confirmed for many that Hutchinson was a coconspirator in the plan to enslave them.

In response, the Massachusetts House of Representatives dispatched a petition to the king demanding his recall. When Bostonians shifted their attention to the issue of taxed tea in October, they swiftly united. Both the Boston Gazette and a town meeting called upon the tea consignees, including two of Governor Hutchinson’s sons, to resign. The consignees refused to do so, and there the matter stood until the arrival of the Dartmouth, the first of three tea ships, on 28 November.

Imperial law required that the tea duty be paid before the cargo could be unloaded and if not paid within twenty days (by 17 December), the cargo could be seized. On 29 and 30 November, mass meetings of perhaps 5,000 people instructed the consignees, who had fled to the well-fortified Castle William in Boston Harbor, to return their cargoes.

Over the next several days, citizens in neighboring towns joined Bostonians in this demand, all to no avail. Following a third mass meeting two weeks later, Boston’s leading radical, Samuel Adams, led a delegation to customs officials demanding that the tea ships be permitted to leave without paying the duty. However, he met with a firm refusal.

The Tea Party and Its Consequences

On 16 December, a day before the tea could be seized by customs officials, over 5,000 people crowded into Old South Church and ordered Francis Rotch, the owner of the Dartmouth, to ask Governor Hutchinson for a customs clearance.

When Rotch returned with word of the governor’s refusal, Samuel Adams announced nothing more could be done to save the country. This was an apparent signal for three groups of men to proceed to Griffin’s Wharf, where the three tea ships had anchored, and throw the tea overboard.

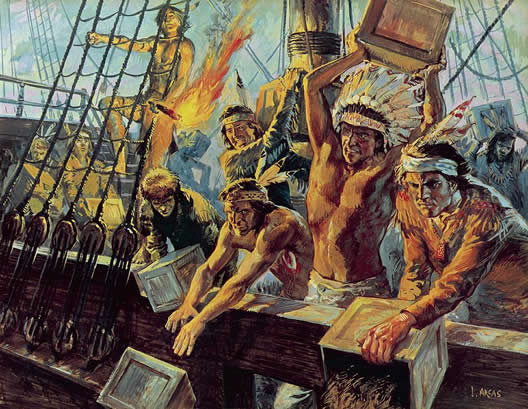

Barely disguised as “Mohawks,” the men methodically threw about 90,000 pounds of tea into the harbor without harming any crew members or customs officials. They destroyed no other property and punished those who attempted to take some of the tea. They and 2,000 witnesses saw these actions as an essential defense of the colonists’ liberties.

Drawing upon the work of several generations of English dissenting writers, notably the early-eighteenth-century essayists John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, colonists of the 1770s saw liberty and power in perpetual conflict.

In that context, they viewed all the actions taken by the British government as unacceptable extensions of power, as part of an effort to subvert their liberties. Destroying the tea, in the colonists’ view, was a measured and appropriate response to an insidious attempt to induce them to become complicit in their own slavery by paying a tax imposed without their approval.

If anyone doubted their wisdom, Boston radicals simply pointed to the British government’s response to the tea’s destruction. When word reached London of the Boston Tea Party, Parliament rapidly passed the Coercive Acts to punish the town of Boston and the colony of Massachusetts Bay.

The port of Boston was closed, town meetings could be held only with the royal government’s permission, the Crown would appoint members of the Council, and troops could be quartered in empty private dwellings. The Coercive Acts convinced many colonists that united action was necessary.

If the British government could take away the liberties of the people of Massachusetts, the liberties of all were at risk. Persuaded that royal officials were intent upon the destruction of self-government, twelve colonies responded to a call for a Continental Congress to assemble in Philadelphia in September 1774, a step that ultimately led to revolution.