|

| Anti-Catholicism |

Anti-Catholicism constituted one of the nation’s earliest and most virulent conspiratorial fears. It continues to linger in the very heart of U.S. popular culture, appearing in radio, television, music, and now on the Internet. Based in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries on Rome’s supposed political power, antipathy toward Roman Catholicism has since the 1960s insisted that Catholicism threatens the most basic tenet of U.S. identity: the personal freedom of the individual.

Roman Catholicism represents the perpetual “Other” whose very mysteriousness and difference maintains a certain distance from U.S. life. Over the centuries this distance has exhibited a rather protean nature to where “anti-Catholicism” serves as a canvas on which non-Catholic Americans paint their hostilities. During the colonial period, anti-Catholicism continued on U.S. soil religious and political conflicts that began in Europe.

During the antebellum period, anti-Catholicism represented the epitome of mental and physical slavery that social reform movements sought to undo, much like their crusades for temperance and slavery abolition. Catholicism’s ready identity with different ethnic groups—Irish and German at first, then Italians, Poles, and French-Canadians after the Civil War—underlined the Church’s inherent foreign character.

|

During World War I Catholicism appeared to many Americans as a traitorous community in their midst. Only with John Kennedy’s successful presidential campaign in 1960 did anti-Catholicism shift to more individual concerns. Now Catholicism is viewed as the last religious tradition capable of inhibiting the personal growth and self-awareness of many Americans.

According to this view, Catholics, despite whatever claims they might make about their Americanness, harbor a hidden agenda that they seek to impose on all other Americans. Historian Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., once remarked that anti-Catholicism was “the only remaining acceptable prejudice.”

Schlesinger pointed his comment toward the nation’s educated elite, but the point could be extended much further. The idea that Roman Catholicism represents a threat to U.S. culture has taken many forms, including a few by Catholics themselves. Mistrust and fear of Catholicism’s hierarchical structures and theological positions continue to animate U.S. life.

Roots in Protestantism and English Puritanism

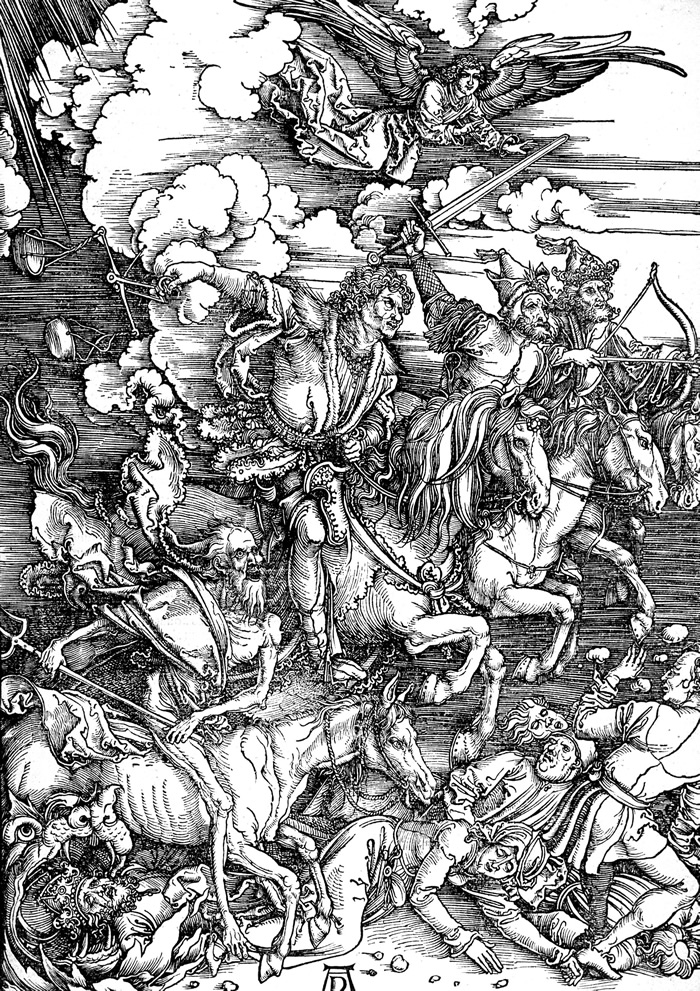

Animosity toward Roman Catholicism is deeply rooted in the history of western Europe as well as that of Christian thought. The apocalyptic imagery of the “Whore of Babylon

While early Christianity read Revelation as a coded text against pagan Rome, the generations that followed often understood the Scriptures as leveling divine judgment against Christian Rome as well. Rome’s spiritual tyranny over Christians enjoyed demonic, not heavenly, support. English Puritanism took the argument even further.

Seeking to purify the Church of England of anything remotely Catholic, anti-Roman animosity became a measure of one’s faith. In other words, resistance to Roman Catholicism constituted a bedrock duty of all real English Christians. The martyrdom of English Protestants during the reign of Queen Mary (reigned 1553–1558) foretold the future if Catholics achieved power.

Elizabethan Puritanism held that Catholicism constituted a threat to English politics as well as the nation’s spiritual climate. The Spanish Armada, the Gunpowder Plot, and later the Jacobite uprisings indicated that Catholics seeking the throne also sought to return England, through force if necessary, to Rome.

Colonial Expressions

The English colonies in the New World reflected these conflicts with Catholic powers. Consequently, many colonies possessed legislation that limited worship opportunities and sometimes voting rights for Catholics.

Some, such as Massachusetts, threatened death by hanging to anyone revealed as a Catholic priest, and even though Maryland was founded as a haven for Catholics, it quickly came under Anglican control, too. English Protestant colonists felt surrounded by Catholic colonial powers France and Spain. They therefore sought to ensure that their own spaces were utterly free of any Catholic contagion.

Fear of the Immigrant in the Nineteenth Century

The disease metaphor became quite popular during the nineteenth century, for Roman Catholicism appeared as metastasizing tumor. Waves of immigrants from Germany and Ireland beginning in the 1820s accelerated the growth of the Catholic Church.

While internally the Church faced growing ethnic conflicts (e.g., German parishes occasionally refused the English-speaking Irish priest assigned them by an Irish bishop), non-Catholic Americans perceived Roman Catholicism as a foreign monolith poised to overthrow the young nation’s democratic system.

It seemed that Catholicism was assuredly un-American. The Church lacked democratic procedures for acknowledging authority, its worship practices seemed clearly at odds with scriptural guidelines, it had attempted the forcible reconversion of Protestants, and its members in the United States were almost entirely nonnative immigrants.

Consequently, anti-Catholics acquired the label “nativists” for their insistence that the foreign-born could not claim to be Americans. Since the Catholic hierarchy often established parishes with specific national identities (e.g., naming parishes after a nation’s patron saint, such as St. Patrick), Catholicism seemed to prevent its members from “Americanizing” completely.

The Americanization issue continued to pester Catholic leaders through the nineteenth century. After the Civil War, immigration shifted from western Europe to southern and eastern Europe. Catholics from these regions— Italians, Portugese, Poles, Slavs, and French-Canadians from Quebec—appeared to be even more resistant to Americanization than the Germans and Irish.

Beyond the immigration issues, Catholicism posed a significant question to U.S. identity. If the nation became filled primarily with Christians belonging to a foreign faith (since the pope, ensconced at Rome, controlled Catholicism), what would become of U.S. institutions like democracy, free enterprise, and freedom of worship? The nativist response took two paths: political opposition and popular culture. Both paths took inspiration from the Puritan slogan “No Popery.”

The Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, better known as the “Know-Nothing” Party because when asked about their political activities they claimed to “know nothing,” sought to elect candidates to local, state, and national offices who would ensure that the United States remained a Protestant and democratic country.

In 1852 Know-Nothings won election victories nationwide, especially in Massachusetts where the governor and all higher commonwealth officials were affiliated. Know-Nothings diluted some of their political power by joining larger national parties such as the Republicans.

Similarly, social reformers interested in abolishing southern slavery and the liquor trade often regarded Catholicism as the epitome of enslavement, suscribing to the view that being Catholic subjected one to physical as well as spiritual slavery. Many Catholics, it was felt, particularly the Irish, seemed unable to turn away from liquor’s appeal.

Reforming U.S. life began, therefore, with opposition to the further growth of Roman Catholicism. Another battleground was the public school system. In the early 1840s, following the complaints of Catholic parents, New York Protestants joined forces to ensure that public schools continued teaching with the King James Version of the Bible.

The mysteriousness of Catholic convent life fostered one of the strongest anti-Catholic messages. Tales of “escaped nuns,” young women claiming that they had been abducted into convent life, proved wildly popular throughout the nation.

Some were published, the most popular of which was The Awful Disclosures

Not only did Catholicism threaten the nation’s political economy, individual Americans stood in danger of being the victim of Catholic “press-gangs” hell-bent on increasing the Church’s membership. In the 1840s a lecture circuit featuring Monk and other escaped nuns, as well as theatrical plays, developed the theme.

As a result, the arrival of Catholic immigrants occasionally resulted in violence. Lyman Beecher’s 1835 “Plea for the West,” a speech in which he claimed Catholics were settling western lands far faster than Protestants and thus threatened to cut off U.S. expansion, resulted in a mob burning an Ursuline convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

In 1844 Philadelphia nativists rioted following rumors that local Catholic parishes were stockpiling weapons for possible rebellious activity. Thirteen people died and over fifty were wounded in the violence. Violence threatened in St. Louis and New York, but did not materialize.

The Civil War offered a respite from anti-Catholic attitudes, as Catholics served in both armies (notably Union general Philip Sheridan) and religious sisters served in medical roles. Even then northern nativists questioned Catholic loyalty when, in 1863, large numbers of Irish immigrants participated in violent draft riots in New York City.

Political cartoonist Thomas Nash captured the anti-Catholic message in an 1871 Harper’s Weekly drawing. It depicted Catholic bishops as aggressive alligators coming ashore to attack Protestant America, suggesting that Tammany Hall was a new Vatican and that Irish immigrant politicians threatened to dismantle public schools.

During the 1880s and 1890s, the American Protective Association (APA) resurrected the Know-Nothing cause. Predominantly located in the Midwest, the APA utilized the same rhetoric but failed to generate the same interest.

It did succeed in casting suspicion on emerging labor unions, often filled with and led by Catholics, and other radical political movements. In the 1880s and 1890s nativist politicians, particularly within the Republican Party, sought to curtail immigration to limit increasing Catholic power in urban areas.

Scientific racism informed these efforts, “proving” that Anglo-Saxons—who were overwhelmingly Protestant—enjoyed biological as well as cultural and religious superiority over the newer Catholic immigrants. Immigration restriction continued to be an issue until Congress established strict limits, aimed primarily at immigrants from Catholic and Jewish areas of eastern and southern Europe, in the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924.

The Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s

The Ku Klux Klan reemerged in 1915 as the primary vehicle for anti-Catholic nativism. By the early 1920s, the Klan had become popular across the nation. Committed to “100 percent Americanism,” the Klan sought to limit the powers of the now well-established Catholic community.

Klan recruiters pursued Protestant clergy, and the Klan moved to reinforce its view of traditional U.S. morality. This included supporting Prohibition, segregation, Protestant-oriented public schools, strikebusting, and boycotting Catholic (and Jewish) businesses.

Significantly, this incarnation of the Klan saw the largest membership numbers, and the 1920s Klan enjoyed national, not merely southern, popularity. Klan voters helped elect sympathetic politicians and passed anti-Catholic measures in Maine, Indiana, and Oregon, as well as other states. Klansmen fought with Catholic groups in workingclass urban neighborhoods in Ohio, New Jersey, and Illinois.

The Klan resurrected stories of “captured nuns” like Maria Monk. It also circulated a fictitious oath—much like Protocols of the Elders of Zion—purportedly taken by the Knights of Columbus

However, the Klan’s popularity quickly shrank after scandals emerged concerning Klan leadership, especially Indiana’s grand dragon, David C. Stephenson. The Klan enjoyed a minirevival during the 1928 presidential election, stirring up opposition to the Democratic candidate, New York’s Catholic and anti-Prohibition governor, Alfred E. Smith.

Contemporary Expressions

With the 1925 Scopes trial in Tennessee, evangelical Protestantism shrank away from public scrutiny, thus silencing an important source of anti-Catholic rhetoric. Evangelical opposition to Catholicism remains to this day, but never incites the same level of popular support.

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), which inaugurated landmark changes in Catholic liturgy and theology (especially concerning non-Catholics), indicated the Church’s new willingness to converse with, instead of repressing, other religious perspectives. The Catholic Church also expressed its appreciation of democratic political processes.

In this new situation, those advocating antiCatholic views, ironically, have often spoken from liberal, not conservative, perspectives. Paul Blanshard’s wildly popular Catholic Power and American Democracy (published in 1948) expressed the point quite clearly: Catholics voted according to clerical direction, instead of individual decision, and this threatened U.S. democratic institutions.

Through utterly democratic processes, the Catholic Church could mobilize its members to limit the religious and political freedoms of other Americans. Although he had studied to be a Congregational minister, Blanshard affiliated himself more closely with secular humanist groups. He believed his argument was nonsectarian since it applied to the political freedoms of all Americans.

Blanshard’s work received praise from mainstream newspapers as well as from leading academics, such as John Dewey. This recalled the antebellum social reformers who feared Catholicism’s social and political influences, not its theological foundations.

Blanshard’s legacy resurfaced in the 1970s and 1980s when Vatican authorities silenced American Catholic academics such as moral theologian Charles Curran. Catholic threats to personal freedom, especially concerning sexuality, have been explored in U.S. popular culture, ranging from the videos of the singer Madonna

The latest expressions of anti-Catholicism use widely accessible language and assumptions to question the Church’s (and individual Catholics’) views on abortion, sexuality, and personal freedom. The hysterical fears of Maria Monk might have faded, but there remains a sense that Catholicism, much like Nash’s cartoon, threatens to overwhelm freedoms and values that non-Catholic Americans hold dear.