|

| Area 51 map |

Made famous by the movie Independence Day

Area 51 (also called “Dreamland,” for Data Repository and Electronic Amassing Management) covers 38,500 acres of land northwest of Las Vegas near Rachel, Nevada, and close to the old Nellis, Nevada, test range. It is nestled within several mountain ranges that provide still more privacy and security.

Nevertheless, television news shows such as Sightings and Strange Universe have produced features on Area 51. Up to 5,000 personnel per day are flown in on chartered aircraft; the lands surrounding the base feature motion sensors, security cameras, and constant patrols by the Wackenhut guards.

|

In 1955, the government gave Lockheed Aircraft’s designer of the U-2 spy plane the task of finding a test base, and after looking at three locations, he selected Groom Lake. Operations commenced later that year under the name “Paradise Ranch” or simply “The Ranch.”

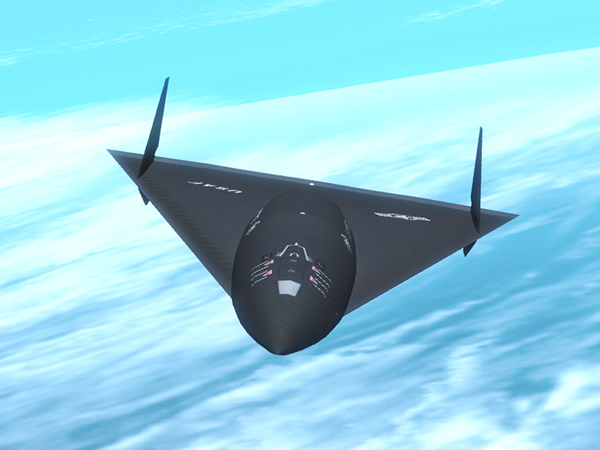

It was officially designated Area 51 in 1958 by the Atomic Energy Commission, but in 1970 the United States Air Force (USAF) took over operations at Groom Lake, and it is currently administered by the Air Force Flight Test Facility at Edwards Air Force Base. The USAF is known to have tested the F-117 Stealth fighter there, and likely the B-2 Spirit bomber was also tested at Area 51. In the 1970s, Soviet MiG aircraft were taken there and examined.

A number of programs that eventually did not produce working aircraft or weapons also were tested there, including cruise missile variants, the Lockheed Darkstar unmanned vehicle, stealth helicopters, and the Osprey. Lights in the sky have been seen from a distance on many nights, which some observers attribute to proton beam systems.

|

| Somewhere in area 51 |

Some claim more than U.S. aircraft are tested there. Robert Lazar, a videotape producer who claims to have worked at Area 51, tells lecture audiences that the facility tests alien spaceships and “reverse-engineers” extraterrestrial technology under the supervision of the mysterious government body “Majestic 12.”

One of the more extravagant claims is that the government is holding aliens—either living or dead—at the base. (A similar claim is made about Hangar 18 at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.) In some cases, these aliens help humans decipher and decode the technology, from which, it is alleged, we have reverse-engineered microwave ovens, cellular phones, and computers.

More exotic technologies are also tested there, according to Lazar and others. The “Pumpkin Seed” and Aurora aircraft have supposedly been operating out of Area 51 for years. But the difficulties associated with reverse-engineering even earthly technologies are substantial.

Even the Soviet Union found it difficult to work backward from captured U.S. aircraft. The notion that humans could create useful weapons or equipment from the debris of an alien vessel is based on the presumption that it would not be so advanced as to defeat any attempts to understand it.

Still others maintain that not only have the aliens helped us reverse-engineer technology, but they actually have taken up residence in the towns surrounding Area 51, such as Rachel and Little A’Le’Inn. According to this view, the aliens act as extraterrestrial flight instructors for humans, possibly in exchange for access to human subjects upon whom they conduct tests.

More recently, an offshoot of this theory claims that conflict broke out between the humans and aliens, which resulted in complete alien dominance of the base at Area 51. Thus, the base and others like it (the supposed alien hideouts at Laguna Cartagena, Puerto Rico, and Archuleta Mesa in New Mexico) have become alien enclaves that humans may not enter. This was to provide the foundation for a worldwide takeover of all humans.

The region around Area 51 is home to “Ufomindand Aliens on Earth,” a small company that specializes in “investigating” the Groom Lake facility. Regardless of the size of the facility and the known operations, the U.S. government refuses to acknowledge the existence of the base.